Doctors honored for helping develop evidence-based treatment guidelines that improve patient outcomes

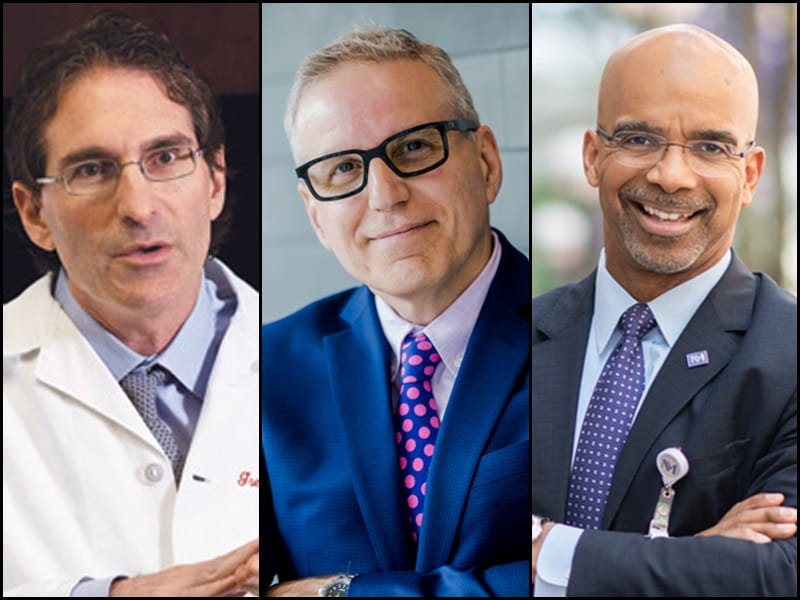

One is a self-professed gym rat, triathlete and jazz connoisseur. Another is a card-carrying member of the Screen Actors Guild who enjoys exploring places on a bicycle. The third runs 30 to 40 miles a week and became a puppy parent during the pandemic.

It's a wonder they have time for anything but their ideas on changing the world of medicine. Leaders in their fields of heart failure and stroke, the three doctors have touched millions of lives with their collaborative efforts over the last 20 years as the brain trust behind developing and supporting Get With The Guidelines. The American Heart Association program provides evidence-based treatment protocols for hospitals to improve quality of care and serves as a platform to accelerate the collection and impact of patient data.

Designed to close the treatment gap in cardiovascular disease, stroke and resuscitation, the hospital-based quality improvement program has sped up the adoption of science practice guidelines from 17 years to within weeks from the practice guidelines being put into effect. Get With The Guidelines includes modules in coronary artery disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, stroke and resuscitation.

For their decades of dedication to improving the outcomes of heart disease and stroke patients, cardiologists Gregg Fonarow and Clyde Yancy and neurologist Lee Schwamm will be honored with Gold Heart awards during the AHA's annual National Volunteer Awards virtual ceremony, which can be viewed by the public live online June 28.

Together, the three physicians have written and inspired more than 600 publications about the impact of GWTG. As a result, the programs are in more than 2,500 hospitals — a third of the nation's hospitals — with 10 million patient records. The data helps create vast national-level databases for advancing scientific research that produces more evidence, insights and patterns for more effective patient treatment.

The award highlights "the importance of teamwork and collaboration, synergy and selflessness," said Yancy, vice dean of diversity and inclusion and chief of cardiology at the Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

"We wanted to build something that was sustainable, something that would have an influence, something that others could use, and ideally we'd look up and see that millions of people have benefited from this."

Getting there

The three men had different journeys to their professions. Schwamm got a philosophy degree from Harvard before changing his career path to medicine and then being "smitten" with neurology. He met his wife in med school, and now they like to travel to other countries and discover cities and their cultures by bike.

The vice president of virtual care at Massachusetts General Brigham Hospital, Schwamm got invited to join the Screen Actors Guild after being "a principal in a union production" when he was featured in a hospital commercial and spoke eight words.

"It doesn't really do that much because, quite frankly, I'm not actually in anything," said Schwamm, adding that he gets free advanced screenings before the SAG Awards. "One day I'm hoping for my big break when Hollywood calls."

Yancy, who grew up in the Deep South when integrated schools were becoming the law of the land, pursued his dream of going to medical school at Tulane University in New Orleans. He was a 20-year-old medical school freshman, carrying a backpack and a basketball. After his first year, he went back to Southern University, a historically Black land-grant university in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to finish his bachelor of science degree at his mother's insistence.

Today, his Chicago office displays not only career awards but bibs from the triathlons he has completed along the way. He calls himself a "gym rat," working out five to six times a week, and a connoisseur of jazz. He also has spent over a decade serving as a role model for ninth- and 10th-graders at a local high school.

"If you knew the demographics of the community that I support, it's a remarkable story that those children are not taking jobs in the service industry but are going to college on full scholarships and are seeking fairly sophisticated careers," he said.

Fonarow, who swam the butterfly and freestyle on amateur teams and was on UCLA's swim team his freshman year before his pre-med lab work interfered, followed along with his best friend's path to medical school. The friend's father was a pediatric orthopedic surgeon and Fonarow, fascinated by science and wanting to make a positive impact, thought medicine was a good career route.

The fifth-generation Californian, who did his medical training at UCLA before joining the faculty, said his passion for work leaves little time for other things. But he enjoys running.

"I do get in 30, 40 miles a week and have done a couple of marathons," said Fonarow, interim chief of the Division of Cardiology in the Department of Medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. "It's a good way to keep in good shape and get inspired. Some of my best ideas have come to me while running."

Grounded from travel during the COVID-19 pandemic brought Fonarow a new adventure, a "pandemic puppy" named Elliott, a now 2-year-old cockapoo.

Collaboration among far-flung colleagues

Through the years, the three doctors have gotten to know each other well. Yancy said he and Fonarow have communicated no less than every other day for years. Schwamm and Fonarow have published 206 papers together, "about 20 papers a year for the last 10 years."

The trio have tried to persuade other medical professionals to collect and share their clinical data and then follow the most up-to-date, evidence-based treatment guidelines to get the best possible quality of care for their patients.

"What united us was our common belief that we could use this approach to shorten, close that process from evidence to practice, shrink it from decades down to years," Schwamm said.

The AHA launched the first national Get With The Guidelines module on coronary artery disease in 2001.

It's hard to say how many lives have been saved by the collective efforts of the trio, the AHA and hundreds of dedicated physicians, nurses and pharmacists, Fonarow said.

"We've tried to quantify it, but it certainly has exceeded our wildest dreams."

Yancy called the enterprise a career investment.

"These are enduring lessons that will last long after the three of us stop doing this," he said.