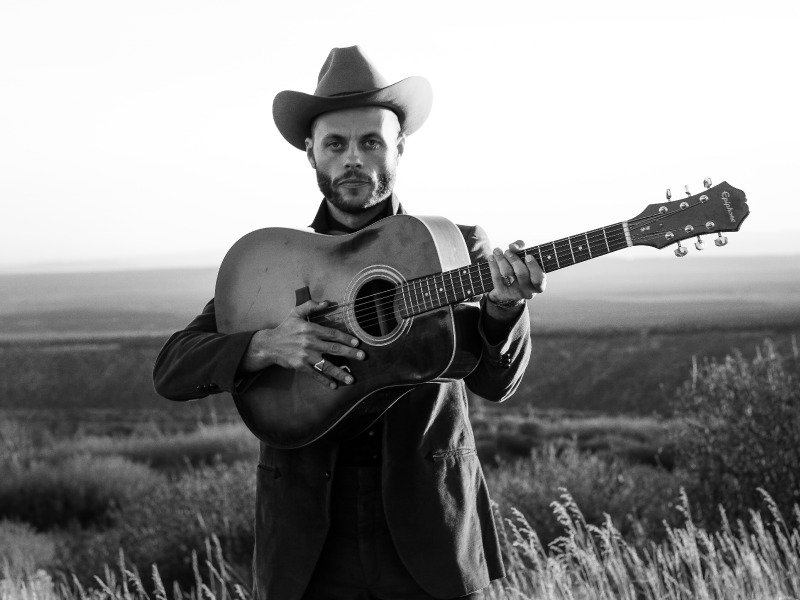

Up-and-coming Texas singer lucky to be alive and still singing the blues

By American Heart Association News

A few years ago, Texas country-blues singer Charley Crockett wrote "How Long Will I Last" about an uncertain love affair. Little did he know the song title would also apply to his struggle with heart disease.

"The cardiologist determined I was one year away from heart failure," said the 34-year-old musician. "It was really, really good luck that I found out what was wrong with me."

Crockett, a descendant of folk hero Davy Crockett, was born with a heart rhythm disorder called Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, or WPW. He spent a month in the hospital as a newborn, but lived most of his life with no major complications.

But as his career took off, so did his health problems. He felt fatigue, shortness of breath and dizziness to the point of sometimes blacking out.

At first, he chalked it up to years of stress living as an itinerant musician. After growing up in a trailer park in South Texas, he spent his 20s riding the rails, sleeping in parks, and performing for spare change in New York City subway cars. By 2016, when Rolling Stone dubbed him one of "10 Artists You Should Know," his work and travel schedule kicked into high gear.

"I was living really hard," he said. "I was getting short of breath, and it was scaring me, but I didn't want to talk about it. I'm a pretty stubborn guy, and I didn't want it to be an issue."

It did become an issue – but only by chance. Last year, when Crockett sought medical advice for repairing a hernia, he listed WPW on his medical history, prompting the doctor to send him to a cardiologist as a precaution for surgery. It was only then Crockett learned he also had bicuspid aortic valve stenosis, a disease where, instead of having three aortic flaps that allow the blood to flow, two are fused together.

An estimated 1.4 percent of the population is born with bicuspid aortic valve stenosis, but Crockett's condition had progressed to a dangerous point. His valves were leaking blood, making valve replacement surgery a necessity.

After researching the issue and consulting with his Austin cardiothoracic surgeon, Dr. Faraz Kerendi, Crockett opted to have open-heart surgery to replace his faulty valve with a bioprosthetic valve created from cow tissue.

While mechanical valves tend to last longer, Crockett chose the cow tissue valve for career reasons: He wouldn't have to take blood-thinning medicine for the rest of his life, which could put a damper on his frenetic performing style.

"I play 90 minutes straight each night, dancing onstage, and you just can't be as active with the blood-thinning medications. That was huge for me," said Crockett, whose most recent album, "Lonesome As A Shadow," has earned national acclaim, including a story in Billboard that compared his song "Ain't Gotta Worry Child" to the music of soul legend Curtis Mayfield. "I've really had to do my research and quarterback the whole thing. … I've realized patient awareness is everything."

Crockett has been resting at home in Austin since his Jan. 22 surgery. For a musician who thrives on being on the go, recovery has been difficult, said Lyza Renee, his girlfriend.

"Charley just naturally has all this energy, so it's been a challenge for him learning how to slow down," she said. "The doctor told him that he had been operating at 65 percent (before the operation). I was like, 'Oh, my goodness! What's he going to be like after?'"

Crockett has agreed to rest up until April, when he'll travel to California to play the Stagecoach Festival, the country-oriented sister event to Coachella. In July, he'll perform at the prestigious Newport Folk Festival.

By then, he'll be ready to sing songs from a new album he recorded just before his surgery.

"I was really worried about the outcome of the surgery, and all that heavy emotion really transferred onto tape," he said.

The new songs include the autobiographical tale, "The Valley," featuring the lyrics: "Now you know my story/I bet you've got one like it, too/May the curse become a blessing/There's nothing else that you can do."

"That's how I see this surgery, as this enormous blessing. It's like, 'You have a cow valve in your heart! You need to take care of that,'" he said with a laugh. "It took something like this to make me realize I have to put my health and my well-being first."

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].