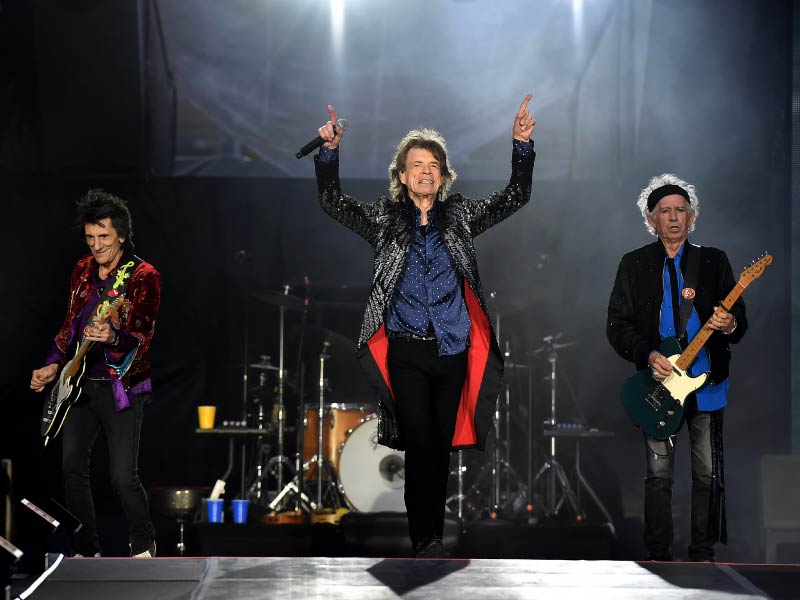

Surgery like Jagger: Doctors explain heart valve problems and treatment

By American Heart Association News

Rolling Stones fans were concerned by the news Mick Jagger needs a new heart valve. But they'll be happy to know that these days most patients in his situation can get what they need — and often without intensive surgery.

While Jagger has not discussed his condition, Rolling Stone magazine confirmed reports that Jagger, 75, needs heart valve surgery. It's scheduled this week in New York. Jagger is expected to make a complete recovery, the band said in a statement.

Jagger has plenty of company. More than 5 million Americans live with heart valve disease. In 2013, the most recent year for which numbers are available, more than 100,000 people had heart valve surgery, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

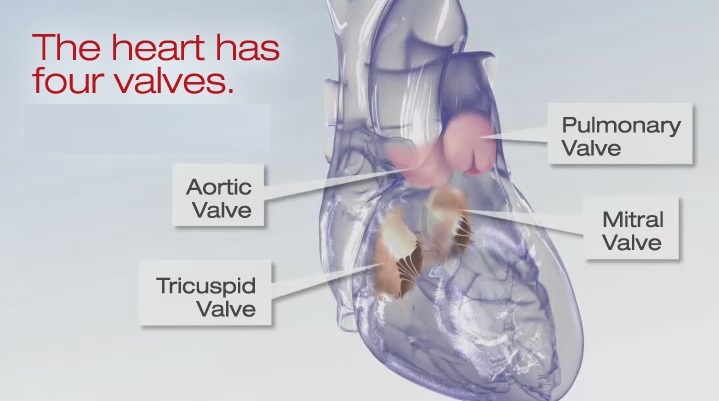

Dr. Catherine Otto, a professor of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle, offered this primer on the heart's four valves – and how they can malfunction.

The two valves on the right side, which pump blood into the lungs, are rarely a problem, said Otto, co-chair of the committee that wrote the latest American Heart Association guidelines on heart valve disease. The valves on the left, which pump blood into the body, are typically the issue when something goes wrong, she said.

If one of these valves narrows, blood can't go forward without the heart working extremely hard to push it, she said. And if a valve leaks, the heart has to pump extra blood to make up for it.

"It's a very delicate structure that with time can become a little bit thicker and get a little bit of scar tissue," said Dr. Robert Bonow, professor of cardiology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago and co-author of those AHA guidelines.

A small percentage of people are born with malformed valves; many live for decades without problems. But even an anatomically normal valve is opening and closing with every heartbeat. Bonow did the math: For someone with an average heart rate, the valve opens about 3 billion times over 80 years.

"It's just one of those things that if you live long enough, these valves will begin to wear out at some point," said Bonow, a past AHA president.

Risk factors include the same ones that lead to heart attacks: high cholesterol, smoking, high blood pressure and diabetes, Bonow said.

"But even people who have no risk factors, including athletes, can develop problems," he said.

Symptoms can include chest pain or palpitations; shortness of breath; fatigue; lightheadedness or swelling in the ankles, feet or abdomen. But the warning signs can be "very subtle," Otto said. (Jagger, in fact, was spotted frolicking with his girlfriend and toddler son in Miami Beach just after the band canceled upcoming tour dates because of his health.)

Otto said the most common symptoms she sees include reduced ability to exercise. Patients get out of breath, fatigued or just don't feel like doing it.

"If they get to the point of actually having chest pain with exertion or shortness of breath or dizziness or passing out – those are really more severe symptoms of the disease," she said.

Worn-out valves can be replaced with new ones made from metal or from animal tissue. And treatment has undergone a "transformative" change in recent years, Bonow said, with the growth of a procedure called transcatheter aortic valve replacement, or TAVR. The aortic valve is on the left side of the heart and releases blood to the body's main artery, the aorta.

Until recently, complicated open-heart surgery was standard. But with TAVR, a replacement valve can be inserted without surgery by puncturing a leg artery, inserting a new valve, threading it up to the heart "and just popping it in place," Otto said.

"It's a very short procedure – it takes an hour or two at the most," she said. The patient is the hospital overnight or maybe a couple of days, followed by a week or two of recovery at home. That compares with six weeks to three months of recovery for surgery.

TAVR is currently approved in people for whom open-heart surgery would be considered risky, although both doctors were excited about a recent study indicating TAVR can produce results comparable to traditional surgery in even low-risk patients.

Also, Otto noted, if the problem is related to the mitral valve – that's less likely in someone Jagger's age – a transcatheter approach is possible, but a patient is more likely to need open-heart surgery.

The good news is that barring complications, heart valve problems are usually "pretty much alleviated completely" by treatment, she said. "There is some risk up front, but the outcomes are excellent."

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].