A stroke slowed Olympic legend Michael Johnson. Responding F.A.S.T. sped his recovery.

By American Heart Association News

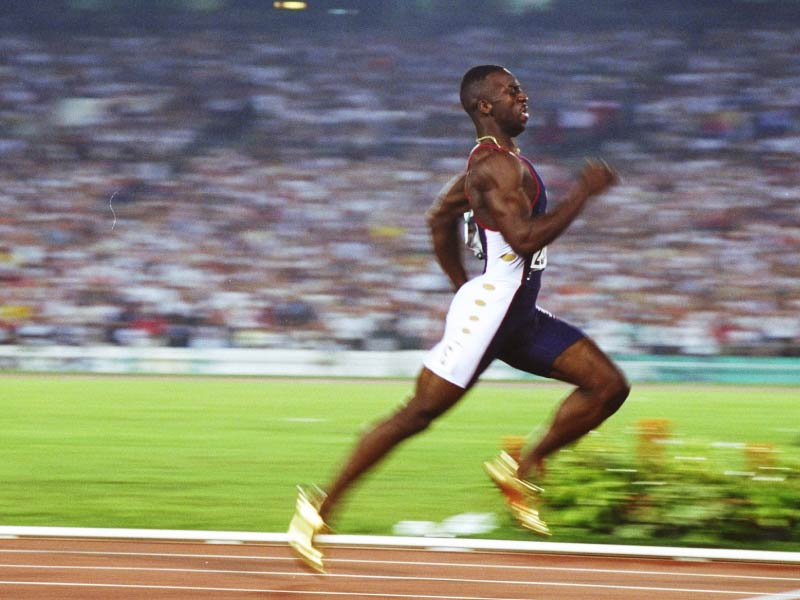

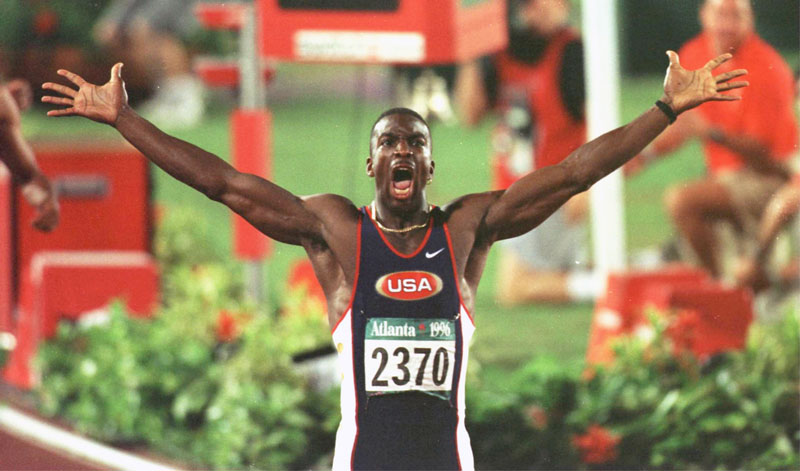

There he was, Michael Johnson, once the fastest person ever to run 200 meters, the man who'd been so confident of setting the world record that he stepped onto the Centennial Olympic Stadium track wearing spikes painted gold.

Only now he was wearing a powder-blue patient's gown and leaning into a walker. He'd just finished a lap around the fourth floor of UCLA Medical Center. It was the start of his recovery from a stroke. When he reached the finish line of his bed, his internal tape measure read 200 meters.

On that memorable night in Atlanta in 1996, he covered the distance in 19.32 seconds. This afternoon in 2018 in Santa Monica, he needed about 10 minutes.

Devastating, right?

Not to Johnson.

At this moment, he knows things can only get better. Although he doesn't know how much, he knows the only way to find out is by pushing his body to its limit. It's a familiar challenge.

"I'll make a full recovery," he tells his wife, "and I'll do it faster than anyone."

Eight months later, only Johnson can detect the differences in his stride pre-stroke and post-stroke. Sure, his recovery was boosted by having the body and mindset of an elite athlete. But doctors also credit the fact he sought help as soon as the symptoms hit.

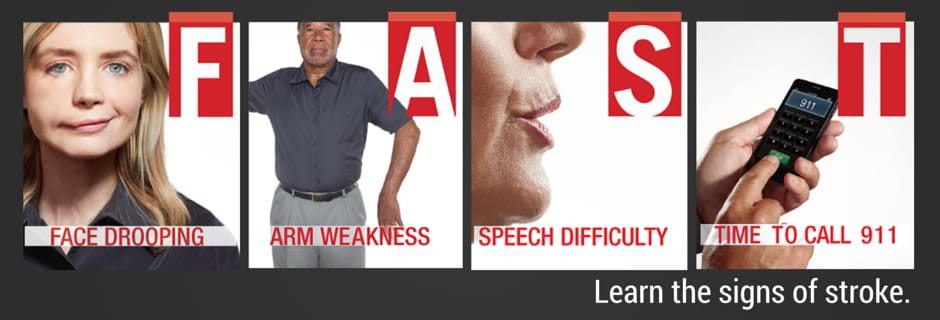

So this May – American Stroke Month – Johnson is helping the American Stroke Association spread the word about recognizing the warning signs of stroke. He's the perfect pitchman for the acronym long used in stroke awareness because it's a word he knows as well as anyone: F.A.S.T.

It stands for face drooping, arm weakness, speech difficulty, time to call 911.

***

Johnson's saga began Aug. 31, a few weeks before his 51st birthday. Life was good.

He's president of Michael Johnson Performance, a facility in a Dallas suburb where everyone from kids to world-class athletes go for training, nutrition, rehabilitation and more. It's a popular destination for college football players before the NFL draft. He's also a motivational speaker and a track analyst for the BBC.

Days before, he helped his son settle into New York for his freshman year of college. With his son's departure turning Johnson and his wife into empty-nesters, they recently moved from San Francisco to Malibu, California. Their new home features a gym befitting an Olympic legend – in its own structure separate from the main house.

That afternoon, Johnson put in 45 minutes of high-intensity strength and cardio exercises. The strain and sweat felt good.

He saw his wife outside with Angelo, their light brown Italian water dog. Johnson walked over to chat, then turned to walk back into the gym.

He stumbled. His left ankle didn't flex.

He hobbled to a weight bench, sat and pondered the workout. What went wrong that might have caused this?

Before he could pinpoint anything, his left arm tingled. Then it twitched.

Johnson struggled into the house and described the sensations to his wife. He reclined on the sofa and called the director of performance at his training facility. Everyone agreed he should see a doctor.

***

His wife drove them to a nearby urgent care center. Doctors there quickly sent him to UCLA Medical Center.

A brain scan came out clear, which wasn't the good news it might seem. The hunt for a cause continued.

Meanwhile, his coordination was getting worse. Fatigue set in. He fell asleep inside the MRI tube. When it was time to get up, he couldn't.

Helped to his feet, his left foot felt numb. He had hardly any strength or motor skills on his left side. He was taken to a private room.

About three hours since this all began, a team of doctors walked in.

***

Stroke is the No. 2 killer worldwide. In the United States, it's No. 5, but a leading cause of adult disability.

While the disease often afflicts people who are older or frail, it also attacks those who are younger – even those who are extremely healthy. African American men are especially at risk.

Most strokes are ischemic, meaning caused by a blood clot in a brain artery. Some are hemorrhagic, involving bleeding in the brain.

Johnson's stroke was ischemic. The MRI showed that a clot had come and gone. But, like a tornado, it left a swath of destruction among the blood vessels on the right side of his brain.

Can they recover? Some? All?

And, if so, how long will it take?

"It's different with each case," the doctor told him. "Fortunately, you got here quickly and you're in very good shape. That works well for your chances. But no one knows."

It's 9 p.m. on a Friday. Doctors wanted his body to heal for the next 48 hours.

Rehab wouldn't begin until Monday.

***

The stroke only affected Johnson's movement. His thinking remained sharp.

On Saturday and Sunday, his mind darted from curiosity about what's next to fears that he'd never walk again. As his wife and nurses helped him get in and out of bed, and to and from the bathroom, he wondered, "Is this my future?"

He again reviewed the workout, seeking a cause. Finding none, anger boiled: "I was doing all the right things – keeping my weight down, working out every day, eating healthy – and I still end up having a stroke."

He cycled through these emotions until settling on the one thing he might be able to control. Rehab.

The thought calmed him. He thought back to when he was 18 and heading to college without having even won a state championship. His goal then was to get the most out of his ability, whatever that might be.

Johnson blossomed into the rare sprinter to win gold at three consecutive Olympics. He became the fastest ever at 200 and 400 meters, setting both records at the 1996 Olympics. No man had ever swept those events. Defending his 400-meter gold became another first. His dominance earned the nickname Superman. When experts rank greatest Olympians, he's part of the conversation.

Now he again wanted to get the most out of his ability, whatever that might be. Like a kid on Christmas Eve, he counted the hours until the start of rehab.

"I've done a bunch of incredible things in life," he thought. "This is going to be another."

***

The physical therapist was a good match: a runner with high expectations for his patients. Especially this one.

He insisted Johnson use the walker for the first loop, a baseline test.

The therapist told Johnson to place his left foot this way, shift his weight that way. He did. His left foot still dragged, though not as much. He felt the slightest bit of heel-to-toe action.

The incremental improvement changed everything.

What others might've considered miniscule loomed large to Johnson. Remember, this is a guy who once "shattered" a world record by 34-hundredths of a second.

He also began to see his therapist as his coach for the most important race of all.

So when Johnson got back to his room and declared that he would make a full, fast recovery, he wasn't merely spouting positivity.

"It's going to come down to hard work and focus," he told his wife. "I know how to do that."

On his way out, the therapist folded up the walker and said, "We're not going to need this anymore."

***

The next day, Johnson walked to the elevator and rode down to the physical therapy clinic. The day after that, he took the stairs.

At home, he did therapy twice a day, mostly in front of a mirror.

While he made great strides, progress wasn't constant. Like all stroke patients, he hit plateaus.

Around Johnson's 51st birthday, the mirror in his gym showed a guy who recently looked and felt 30 but now felt 90.

"I'm not Superman anymore," he thought. "But every day, I'm getting better."

At six weeks, his wife no longer detected a limp. Around four months, Johnson considered his gait smooth.

"My left side dynamic stability is still not equal to my right side," he said in February, six months after the stroke. "I'm still on this journey to get back to 100% of where I was before."

***

Johnson continues to eat healthy and exercise regularly, and he's trying to manage stress better.

He still has some numbness on the side of his left hand, in his left pinkie finger and on the bottom of his left foot in a space mid-foot between the big toe and the second toe. Feeling may return, but he's accepted that it might not.

He's also accepted not knowing what caused his stroke.

Despite extensive testing, doctors never found a source. This happens in about one of every three strokes, a classification called cryptogenic. The term simply means no one knows the cause.

"It shouldn't have happened the first time," Johnson said. "Hopefully it won't happen again."

He also hopes sharing his story will help others.

Johnson tweeted about his stroke soon after it happened. He continues talking about it because he realizes he can make a difference, especially because he has legions of fans around the world.

"Being a stroke survivor is now part of who I am," he said. "I want people to understand it can happen to anyone and that there are ways to minimize their risk."

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].