Meet 'Model 2' Christina, the happier, healthier version

By Nancy Brown, American Heart Association CEO

Christina Herrera seemed surrounded.

Her mom died of diabetes at 55. Her dad lost his legs below the knees because of diabetes. Diabetes altered the life of her older sister. And, in 2016, the disease claimed the life of her baby sister.

But here's the thing: They all had type 1 diabetes, which is usually diagnosed in youth.

Because Christina was in her early 40s, she thought, "I'm in the clear."

A multi-sport athlete in high school, she still worked out occasionally – enough, she hoped, to compensate for the sodas she slurped and the Mexican feasts she enjoyed at frequent family gatherings.

Then the doctor said she was "prediabetic." Not type 1, but type 2, the kind often traced to lifestyle choices … such as sodas, pork tamales slathered in salsa, and refried beans.

Then came the heart attack symptoms.

And the triple bypass.

Yet that's all part of Christina's backstory. Because the focus of this tale is what came next, the renewed friendships that sparked her recovery and a new lifestyle, one that includes encouraging others – especially fellow Hispanics – to avoid or conquer type 2 diabetes.

***

Christina enjoyed her time as a student at North Dallas High School so much that she returned as a teacher.

When her 37-year-old sister's heart stopped as a complication of her diabetes, Christina asked a coach for some fitness tips. He helped her design a regimen that included lifting weights and running. She also started watching her diet.

"But I'll be honest," she said. "If the coach wasn't watching, I had my bag of potato chips. I'd go to my sister's house and not think twice about what I was putting into my body. I was telling myself it was OK because I was working out."

Around the start of the 2017-18 school year, a checkup showed she was prediabetic. The doctor encouraged Christina to keep exercising and to pay closer attention to her diet.

"But I was so naïve about what that meant," she said. "I thought that if I kept eating salads, that was good enough."

In the final weeks of that school year, as Christina walked the stairs to her second-floor classroom, her heart raced. Breaths became short. She began sweating. When she got to her room, her stomach felt upset.

She told the father of her son. Knowing Christina's family history, he persuaded her to visit the school nurse. The nurse checked Christina's blood pressure.

"I have to call an ambulance," the nurse said.

***

Initial tests showed no heart damage.

Considering her family history, they insisted she stay overnight for more tests. She agreed, with a caveat: She needed to be released in time to attend the graduation ceremony Saturday.

A stress test led to a cardiac catheterization procedure. The doctor injected dye to observe blood flow. Watching the screen, he said, "Christina, you're not going to make it to work this week."

They discussed her options, settling on the bypass operation.

"The surgery is tomorrow," the doctor said. "Your summer break has officially started."

***

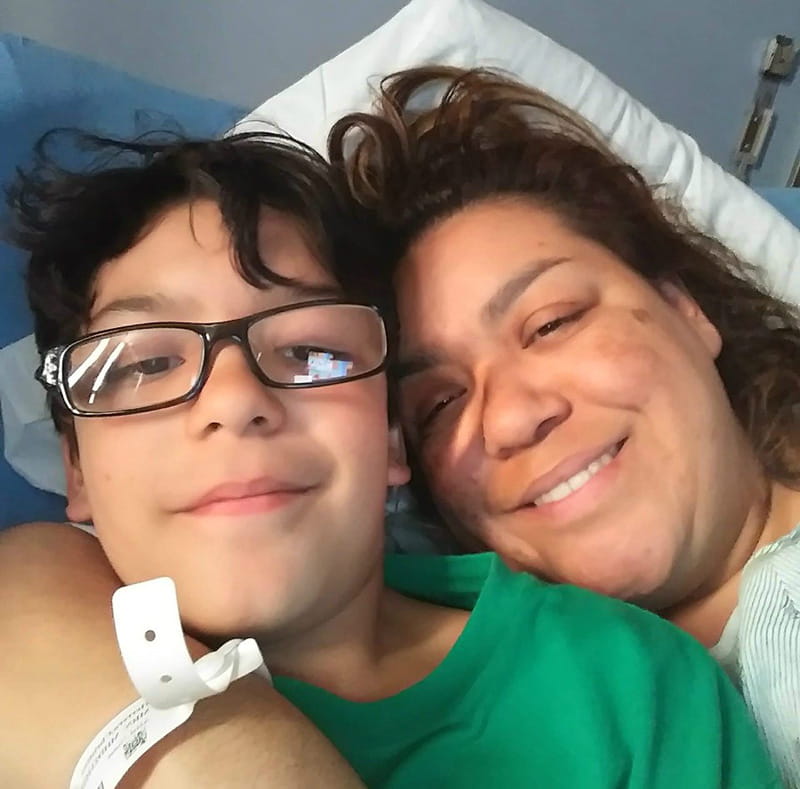

In the hospital, Christina learned she was no longer prediabetic. She had type 2 diabetes.

Now it was time to get serious about controlling her diet. Except, she didn't know how.

"C'mon, Christina – you're a teacher, figure it out," the doctor said.

Deep dives into the websites of my organization, the American Heart Association, and the American Diabetes Association taught her to read food labels. She downloaded an app to track her calories and sugars.

The day she got home from the hospital, she overhauled her pantry and refrigerator.

"I started asking myself, 'Do I really want that sweet bread? It has 12 grams of sugar. A cup of strawberries has two,'" she said. "Decisions like that became a no-brainer."

Another no-brainer: A similar devotion to exercise.

***

The coach who'd helped her before was now working in another state. Nobody she was close with was into working out.

Thoughts of who could help her percolated as she scrolled through Instagram posts by two people she'd gone to high school with, Juanita Cano and Rey Alvarez.

Christina and Rey were workout buddies. Sort of. While they ran races together, they lived too far apart to train together. So each posted a picture after a workout, challenging the other to keep up.

"I want to hang out with them," Christina thought.

Instead, they came to her.

***

Once Christina arrived home from the hospital, she posted on Facebook that she was recovering from a triple bypass. Juanita saw it and gasped. She couldn't believe that "someone in our age bracket – someone we knew as a jock! – had deteriorated to that state."

Juanita asked if she and Rey could visit.

"Of course!" Christina said, all the while thinking, "Maybe they can be my mentors."

The first visit was purely social. During a second visit, Juanita and Rey asked Christina to run a 5K.

"Can people in my condition even do that?" Christina said.

"Do it!" her doctor later said. For encouragement, he mentioned another patient, a Marine who'd run a 5K two weeks after heart surgery.

"But I'm not a Marine," Christina replied. "I'm just a teacher looking to get back to work."

"I'm more hesitant for you to get back to work than I am for you to start running," he said.

By September, Christina was posting pictures from her workouts on Instagram, tagging Juanita and Rey.

In December, the trio crossed the finish line together. They might've all held hands except Juanita's were capturing a video documenting Christina's tearful burst of emotions.

"It was a nice feeling," she said. "I'm almost looking forward to feeling it again."

On Dec. 14, the trio will be back at the starting line.

Only this time, they're running a 10K.

***

The entry form of her first race asked Christina why she signed up.

Her answer prompted a TV interview. The station has since featured Juanita, focusing on her running a race or competing in a triathlon about every other weekend despite a rare neurological condition that leaves her in constant pain.

Rey, meanwhile, is just getting back into running after donating a kidney to his brother.

Medical challenges aren't all that binds them. They also share Hispanic heritage. Between their genes and their cultural lifestyle, they're at an elevated risk of high blood pressure, high cholesterol and type 2 diabetes, all of which elevate risks for heart disease and stroke.

For Christina and Juanita, it's one thing to deal with their family questioning their devotion to exercise.

The bigger challenge is navigating the unhealthy foods constantly being offered – and the blowback that comes with turning it down. They've been accused of turning their backs on their family and of acting as if they're too good for them.

"Christina's family is similar to mine in that nobody is cheerleading for you," Juanita said. "They want to feed you, make you fat."

Christina admits to struggling with cravings when she's around her comfort foods. Her best option is avoiding gatherings. It's always tough, especially this time of year.

"But I'm OK with it," Christina said.

The women have come to rely on each other. Last month, Juanita finished a Half Ironman and the first person she saw was Christina.

"I started bawling," Juanita said. "She was exactly who I needed to see."

Christina’s willingness to share her story also led her to become among five ambassadors of my organization’s new campaign, Know Diabetes by Heart.

Although Christina has run three 5Ks, and her diabetes and high cholesterol are under control, she knows how fragile it all is. Her dad died this summer from complications of his diabetes.

"The way I look at it is that I had a lifetime of bad habits," she said. "So now I'm calling myself Model 2." Laughing, she added, "Not type 2, Model 2!

"I feel better, breathe better, don't get tired," she continued. "When I go up the stairs at high school, I challenge my students – and usually win. I like the new me. I'm proud of how far I've come."

A version of this story also appeared on Thrive Global.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].