NYC cardiologist – and COVID-19 survivor – helps Hispanics fight the virus

By American Heart Association News

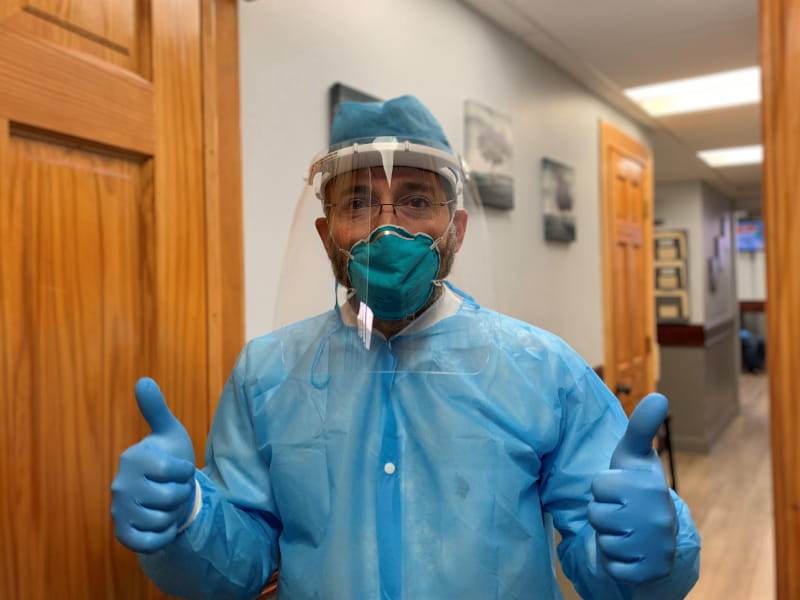

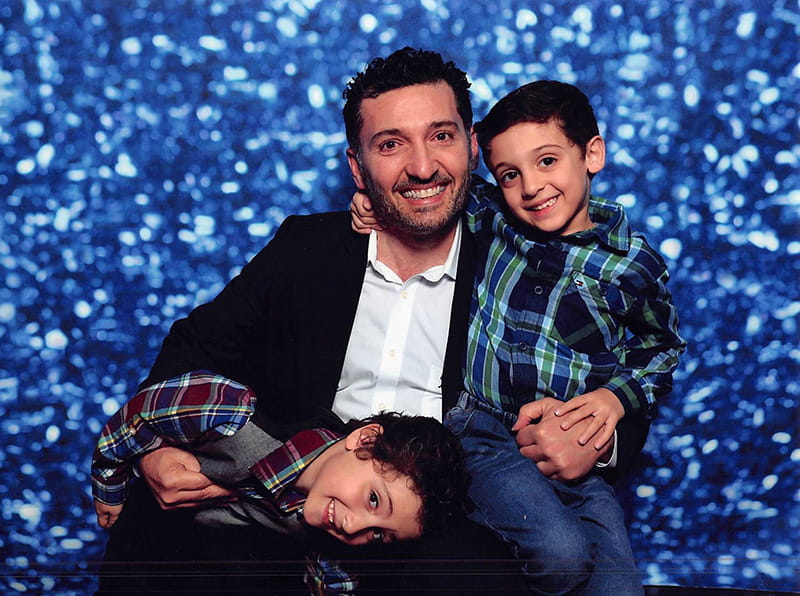

New York City cardiologist Dr. Samer Kottiech became a "hardcore COVID expert" the hard way.

He developed symptoms he didn't immediately recognize as COVID-19: redness and pain on the small toes of his left foot and his index finger. Chills and severe muscle aches presented two days later, followed by high fever and loss of sense of smell.

"I felt like un carro me pasó por arriba (like a car ran me over)," said Kottiech, who tested positive in March and has now fully recovered. "I felt horrible pain and I'm not a guy who complains. As you can imagine, because of the high fever, sometimes I couldn't even get out of bed."

Kottiech believes he contracted the virus at an outreach Washington Heights medical office where he works twice a month. Despite his illness, on the days he could get up, Kottiech screened and treated his patients using telemedicine. About 98% of his practice is Hispanic, the group with the highest percentage of deaths of any racial group in New York City, according to that state's health department. Kottiech knew he was needed.

"I had a lot of patients that were panicking," he said. "I've been trying to help my Latino community, which has been neglected. Some had symptoms; some of them had heart problems that we could not attribute to COVID-19 at the time, but we learned later there are implications of the heart from the virus. During that time, I had to diagnose and treat via video camera without a stethoscope. It was a learning process where I had to apply both art and medicine, because this has been a learning process and sometimes all you can do is go with your gut feelings."

One of those highly troubled patients was Fermina Gomez, whose husband of 26 years died on April 5 of complications from the virus. Although Gomez tested negative, she developed symptoms around the time of her husband's death, including fever, body aches, joint stiffness, headaches and a fast heart rate. Gomez reached out to Kottiech, who treats her for high blood pressure, or hypertension.

"I was really scared," said Gomez, who has a 15-year-old daughter. "I was having symptoms, and I had been exposed. I couldn't sleep thinking that I could not die and leave my daughter by herself.

"I call Dr. Kottiech my guardian angel because he's the only one that gave me a hand when I needed it," she said. "He treated me emotionally and psychologically and he adjusted my medicines. This thing is a monster, but in my most desperate and difficult times, Dr. Kottiech treated me with so much empathy."

The disproportionate number of COVID-19 cases and deaths among Hispanic and African American populations in New York City has served to highlight economic and health care disparities that long predate the crisis.

"We know that Latinos and African Americans are more susceptible to suffer from hypertension, obesity, diabetes and coronary artery disease, which means these populations have underlying conditions that put them more at risk of developing severity of COVID," Kottiech said.

"They don't have access to healthy food, which is one of the reasons they have those conditions," he said. "They also often don't have college degrees, don't have jobs where they can work remotely, sometimes have no insurance, and sometimes are afraid to call 911."

In New York City, the Hispanic community currently accounts for 34% of COVID-19 fatalities despite being 29% of the city's population, according to the state's health department.

In the early days of the pandemic, the medical community believed COVID-19 was mostly a respiratory disease, with coughing initially and pneumonia as a complication. But doctors now have evidence that the virus can impact several organs, including the heart.

Among COVID-19 patients in China, cardiac problems have been a prominent feature of the illness in 20% to 30% of the hospitalized cases and contributed to 40% of the deaths, Kottiech said.

Patients with lung disease and shortness of breath experience diminished oxygen levels, which can lead to cardiac issues. Patients might experience an immune response called a "cytokine storm," in which the body attacks its own cells and tissues and can affect the heart muscle and cause congestive heart failure, Kottiech said. This inflammation also can trigger blood clotting, which is especially dangerous in people with underlying heart conditions.

"COVID toe," Kottiech's first symptom, is believed to be a tiny clot affecting the circulation in the small capillary vessels at the end of fingers or toes. (Abnormal clotting in young adults may be associated with stroke as a severe complication of COVID-19 in some people.)

"If you have redness in your toe, for example, I'm not necessarily telling the patients to go to the ER with that, but ask your doctor," Kottiech said. "Everyone should learn about the disease so they can be more proactive about seeking help. This is a very scary monster, and there's still a lot we all need to learn about it."

Editor's note: Because of the rapidly evolving events surrounding the coronavirus, the facts and advice presented in this story may have changed since publication. Visit Heart.org for the latest coverage, and check with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and local health officials for the most recent guidance.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].