He's run 132 marathons. That's nothing compared to other challenges he's faced.

By Nancy Brown, American Heart Association CEO

As George Banker prepared to run his 103rd marathon – yes, 103rd – he felt a sharp pain in his right shoulder.

Doctors traced the problem to a faulty heart valve. It needed to be repaired or replaced – however, not quite yet.

A year and a half later, as Banker prepared to run his 110th marathon, the cardiologist said it was time. Eight weeks after undergoing open-heart surgery, he was running again.

Banker was up to 117 marathons when the pandemic hit. By October, he couldn't tolerate the layoff. So he ran a virtual marathon. The next week, he ran another. And so on, stopping after 14 marathons in 13 weeks.

April is Move More Month for my organization, the American Heart Association. The purpose is to encourage everyone to improve their physical and mental health by moving their bodies. Banker is obviously an extreme example, someone whose activity level seems unrelatable.

Except, there's more to his story.

Like the addiction – alcoholism – that preceded what could be called his addiction to running.

And the perseverance he's modeled in more ways than reaching all those finish lines. This is a man who earned a college degree in accounting by taking classes for three hours per night, four nights per week for eight years … while working full time.

So hopefully his story can inspire anyone to do anything.

"Don't ever listen to anyone who says you can't do something," he said. "If you've got some limitations, just ask yourself, 'How do I get around them?'"

***

As a youth in North Carolina, Banker learned a lot from his uncles.

Uncle Calvin taught him to fix pretty much anything under a car's hood. That was intentional.

Uncle Robert gave him a glimpse of hard drinking. That was young George being observant and precocious.

"I'd get his whiskey bottles, wash them out and put tea in it so I could pretend I was drinking," Banker said.

By the mid-1960s, Banker's family had moved to Philadelphia. He carried a briefcase to high school, toting a flask of rum amid his pens and papers. On a senior class trip to Washington, D.C., he brought 24 oranges injected with vodka.

After high school, he joined the Air Force. He soon found himself in Japan chugging from thigh-high bottles of a sweet port wine.

The next stop was Thailand. "That's when the drinking started to increase."

A 1972 picture from Guam shows Banker standing beside a ping pong table that looks like an aisle in a liquor store. He recalls polishing off an entire bottle of bourbon that day.

Months later, Banker – just 22 – developed a bleeding ulcer. It flared again when he returned to the United States, prompting an operation that cut away a chunk of his stomach.

"You'd think I would've learned my lesson," he said. "Nope! Four months later, I started drinking again."

The Air Force eventually transferred him to Andrews Air Force Base in the D.C. area. In 1977, carrying the rank of technical sergeant, Banker left active duty and took a job at IBM.

By 1982, he'd begun his long, slow pursuit of a degree from George Washington University. Although he'd given up hard liquor, he often drank beer with colleagues after work, sometimes in a hotel bar. During one of those sessions, Banker realized the bottle in front of him cost the same as a six-pack at a store. Just like that, the whole notion of drinking seemed ridiculous.

"I left that half-beer on the table and walked away from it," he said. "I haven't touched a drop since."

Meanwhile, something else in his life had changed.

He'd started running.

***

Every summer, Banker's office held a picnic that included a 1-mile fun run. When he heard that a particular director won it every year, Banker laughed.

"That old man?" he thought. "I can smoke him in a heartbeat."

Yet at 32, only a few years removed from active duty in the Air Force, Banker struggled to run a mile. That director again won the race. Banker's consolation prize was discovering that his colleagues had a running club.

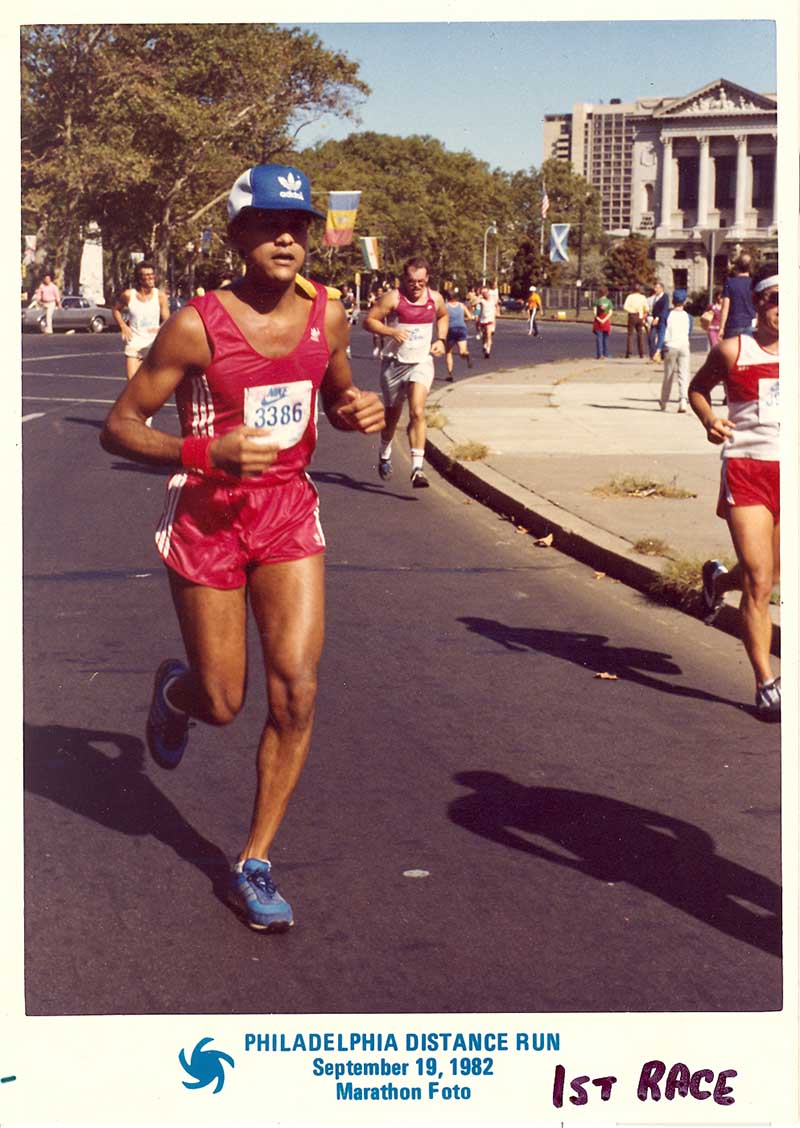

He joined in June and ran a half marathon (13.1 miles) that September. The following April, he made his debut at the full marathon distance of 26.2 miles.

"It was real ugly," he said, laughing, "because I did all the wrong things right."

A friend in the running club gave Banker a marathon training plan. Soon, he was hooked on competing against himself.

At the 1988 Houston Marathon, Banker zoomed to the finish in an impressive 3 hours, 4 minutes, 32 seconds. Being so close to the three-hour barrier, he ran a whopping six more marathons that year … without ever beating 3:04.

"I got depressed, then decided to just enjoy running," he said. "Then the number of races started to add up – 50, 60, 70."

And with his degree in accounting, Banker devotedly tracked all his running numbers.

***

In 2015, Banker's infatuation with numbers caught up to him in the gym at Fort McNair Army Base.

Pushing to get to 10,000 strides on an elliptical machine, he came close, only to climb away dejected and exhausted. A few days later, he came even closer, leaving even more dejected and exhausted.

The pursuit seemed to take a toll. His running times slowed. Then, during a race, his right shoulder hurt so much that he had to lean over to ease the pressure.

Banker knew that such a sensation on the left side could mean a heart problem. He was especially wary because of a family history: His mom had a triple bypass and her mother had heart disease. Since this pain was on the right side, he was certain it came from the elliptical. So he toughed it out.

Weeks later, he felt ill sitting at his desk. He tried to sleep it off, only to wake up dripping with sweat. He got on the ground and pain shot across his shoulders.

"But nothing on the left side," he said, which is why he took a shower, drank a sports drink and went to work the next morning.

A few days later, the pain returned. It was so intense that Banker went to see a doctor for the first time since his days in the Air Force.

***

The doctor insisted Banker start taking medication for high blood pressure and several related issues. More tests were needed to determine the extent of his heart problem.

Banker delayed the tests to run his favorite race, the Marine Corps Marathon. Keeping a promise to his wife, Bernadette, he finished in his slowest time ever (6:50.17).

When the tests revealed his faulty mitral valve, he told Bernadette: "This is my wakeup call. I'm going to do all the right things."

He canceled two upcoming marathons and a 50-mile race. He also made a spreadsheet to track his blood pressure. He later monitored his heart rate. So he knew it was elevated, but didn't realize what that meant until his next checkup, when a nurse asked, "Did an ambulance bring you here?"

That was the day the doctor said it was time to operate.

In 2017, doctors were able to repair his valve, rather than replace it. The operation was expected to take four hours, but lasted seven because of a problem that required a blood transfusion. His next marathon came 13 months later.

***

Early in the pandemic, Banker was running about 20 miles a week. Then he asked his coach – the friend who'd plotted Banker's first marathon training plan – to guide him back up to marathon-readiness.

Soon, he was running 66 miles a week.

He also began looking into virtual races. They cost about $30 and included a shirt and a medal. He got a kick out of running his usual routes and earning swag from cities as far away as Toronto and Des Moines, Iowa, and events with names like Swamp Rabbit and Alien Escape.

His streak might've ended sooner if not for a misunderstanding about a marathon from the Four Corners area, the spot where Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico connect.

"I thought I signed up for one race," he said. "But when the package came in the mail, there were four different bibs."

Starting Oct. 3, Banker ran a marathon for 12 straight Saturdays. He ran the finale only four days later, on Dec. 23.

He gave up the streak for a simple reason: "I don't like cold weather." (Nonetheless, he was back at in January, notching No. 132.)

It's worth noting that Banker's virtual marathons weren't always 26.2 miles.

He often ran 30 so he could climb a massive hill earlier, when he was fresher. Yet he always stopped his timer at 26.2 – for accounting purposes, of course.

***

In the mid-1980s, Banker turned a loosely organized track meet for IBM's runners into a full-scale event. He remained in charge for nine years. That same weekend, many D.C.-area runners participated in Lawyers Have Heart, benefiting the American Heart Association. Since 1995, Banker has been a fixture at the AHA event. This year, it'll be held virtually June 11-13.

Truth is, Banker is a fixture at most races around D.C.

He's been writing about the local scene for the Runner's Gazette since 1983. Since 2003, he's led operations for the Army Ten-Miler.

He's best linked, though, with the Marine Corps Marathon.

For fun, Banker began cataloging the times of every runner for every year of the event. He still does it, though now as the race's historian. He’s also written a book, “The Marine Corps Marathon: A Running Tradition,” that’s filled with inspiring stories and, of course, plenty of numbers.

In 2011, going into his 27th running of the race, Banker was inducted into the Marine Corps Marathon Hall of Fame. He's up to 36 finishes, the latest coming during his pandemic streak.

Why does an Air Force vet who works for the Army race love the Marine event? Well, his dad served 24 years in the Marines and his stepdad served 30 years. Plus, the race is known as "The People's Marathon" and is widely considered among the most beloved events in the country.

***

At 71, Banker half-jokingly said his goal these days is becoming "a better slower-runner."

"It's not as easy as it sounds," he said. "I've had to get adjusted to this new body since the heart operation."

He's treating his new body differently, too. He's tweaked his diet, such as giving up meat for veggie burgers. A bigger change is his willingness to visit doctors. He now encourages others to "listen to your body."

"The first sign you get, if you don't take care of it, you might not get another one," he said.

Yet don't be fooled by his easygoing attitude. There's still a competitive streak in him – one that manifests, of course, in numbers.

USA Track & Field divides runners by age, using five-year groupings for adults. The Masters series begins at 35-39. Every time Banker moves up a rung, he pushes himself at least once to see how fast he can still move.

"Sometimes," he said, "you've got to go for it."

Note to D.C. runners: Banker enters the 75-79 age group in December 2024.

A version of this story appeared on Thrive Global.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].