He keeps pursuing – and answering – big questions about the brain, body. His latest: A portable MRI.

By Nancy Brown, American Heart Association CEO

As a neurologist working mostly in an emergency or intensive care setting, Dr. Kevin Sheth often found himself forced to decide quickly what he thought was wrong inside a patient's brain.

The treatment would be so much easier – and so much better for the patient – if he could peek inside the skull, Kevin thought, echoing the sentiment of doctors throughout time.

The arrival of CT scans in the 1970s helped. Decades later, MRIs made it better. But some patients can't get to the machine. If only there was a way of bringing the machine to them.

It was one of many big questions the young neurologist aspired to answer.

As his career progressed, Kevin developed a knack for taking on paradigm-shifting challenges and forming partnerships. Both are evident in the creation of a portable MRI machine.

The Food and Drug Administration approved it last year. It's now available in a small but growing number of hospitals, including Yale New Haven Hospital, where Kevin works.

This story, however, is about more than the machine or Kevin. Ultimately, it's about pursuing something bigger and better, and the sacrifices made along the way.

And it begins in Palitana, India, a small town near the Arabian Sea.

***

Palitana is at the base of a mountain that features more than 3,000 temples carved in marble. For about a millennium, members of the Jain religion have made pilgrimages there.

Yet the first act of this story involves a pilgrimage headed the opposite direction.

Navin Sheth, Kevin's father, left his childhood home there dreaming of becoming a doctor. He studied chemistry in college in Mumbai, then immigrated to the United States. He waited tables while living upstairs in a church. Shifting his focus to business, he earned an MBA.

Navin met Sucheta, a computer programmer from Mumbai, in the U.S. They married and started a family. While Navin rose to chief financial officer of a construction company, Sucheta raised and inspired Kevin and his younger brother, Kinjal (who became a critical care pulmonologist).

Kevin excelled at school, even skipping a few grades. Virginia Commonwealth University offered him a full scholarship for eight years, covering undergraduate and medical school.

"But I wasn't 100% sure that I wanted to do medicine," he said.

He went to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. An interest in psychology led him to the then-emerging field of neuroscience. He landed a spot in the lab of the department's founder, Dr. Sol Snyder.

"That was where I began to learn what it meant to be a rigorous scientist – how to formulate questions and how to be your own toughest critic," Kevin said.

During medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, Kevin saw serious gaps between what patients needed and what neuroscience could provide. Seeking to help bridge those gaps, he went to Boston for training at Harvard's teaching hospitals.

Thrown into the rapid-fire environment of intensive care, he went from intimidated by the fast pace to craving it. He especially liked how quickly the high stakes bonded him with patients and their families.

Yet it was his own family that sent him back to Baltimore.

***

His wife, Dr. Sangini Sheth, was an OB-GYN at Johns Hopkins. Kevin wound up becoming the first neurologist on staff at a renowned trauma center across town at the University of Maryland.

He frequently saw patients with a swollen brain. It bothered him that the best solution was removing part of the skull to give the brain room to expand.

"It's pretty medieval," he said.

Curious about possible emerging treatments, he found a researcher, Dr. J. Marc Simard, and an entrepreneur, Sven Jacobson, making great progress.

"His science happened to be at the stage where it could potentially be translated to human patients," Kevin said. "So we started working together."

With funding from the National Institutes of Health, their work led to the development of a drug to reduce brain swelling. A clinical trial began in 2013.

Getting that far is impressive for anyone, especially a first-time investigator. Still, it was only the starting line for the most important race: earning FDA approval.

"There's maybe a 1 in 100 chance, so I had to be humble enough to realize that 99 times it doesn't work," he said. "But I also held out hope that maybe this is the one."

The project (known as "CHARM") is in the final stage. If all goes well, the FDA will review it in about two years.

***

Meanwhile, Kevin's career path swerved again.

Sangini, a Connecticut native and Yale graduate, was lured back to her alma mater. While he would eventually join her on staff at Yale School of Medicine, he first took a sabbatical to pursue another question he'd formulated.

It involved a particular subset of patients: those who've had a brain bleed (hemorrhagic stroke) and have a common type of irregular heartbeat called atrial fibrillation. He simply wanted to know whether a blood thinner or aspirin was more likely to prevent a second stroke.

He pitched the idea to Dr. Hooman Kamel, the chief of neurocritical care in the department of neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York.

Working together, and funded by the NIH, this clinical trial (known as "ASPIRE") is also in the final phase.

***

To best appreciate how much science treasures pictures of the inside of a brain, consider this: The CT scan was such a leap forward that its developer won a Nobel Prize in 1979. The next leap was the MRI; its developers received a Nobel Prize in 2003.

Since MRIs became common, engineers and physicists have sought a way to shrink the machine enough to put it on wheels.

Like others in this nascent field, Kevin thought they were going at it all wrong. He formulated this question: How weak of a magnet could produce an image good enough to make a trustworthy diagnosis?

By now he was founding chief of the Division of Neurocritical Care & Emergency Neurology at Yale. He often spoke about his idea for a portable MRI. One such speech was for Yale faculty and trainees. It also was open to the public. Among the attendees were a few employees of 4Catalyzer, a medical device incubator based 20 minutes away. Their presence was no coincidence.

Company founder Dr. Jonathan Rothberg already had revolutionized DNA sequencing and one of his incubator startups was creating a way for cellphones to take ultrasound images. Next on his wish list: a portable MRI machine.

"They had already recruited the most brilliant engineering types from all over the place to start working on this," Kevin said. "I had this incredible opportunity to work with a world class team to translate an engineering innovation to a patient's bedside."

***

While Kevin helped developers understand the practical parameters, Rothberg launched a startup to fund the project.

Not among the investors: Kevin.

"I decided early on not to have any formal affiliation with the company," he said. "It was important to me to stay on the academic-scientific side and to keep that very transparent and clear."

A key teammate for Kevin on the academic-scientific side was Dr. W. Taylor Kimberly, chief of the Division of Neurocritical Care at Massachusetts General, one of Harvard's teaching hospitals. Kevin jokes that they are "scientific brothers," a pair of ICU neurologists with complementary skills.

Once a prototype of the portable MRI was ready, Kevin was eager to oversee a clinical research project. He sought funding from the NIH. Not only was it rejected, "the feedback we got was that it was not believable, not feasible," Kevin said.

He submitted nearly the same grant request – "I changed maybe two words" – to my organization, the American Heart Association. Our reviewers loved it and funded the grant.

(It's worth noting the NIH turns down more requests than it funds. Also, it's common for different sets of reviewers to make opposite decisions on the same project.)

***

When Kevin told his Yale ICU colleagues they were getting an MRI on wheels, "they looked at me, like, 'What are you talking about?'" he said, laughing.

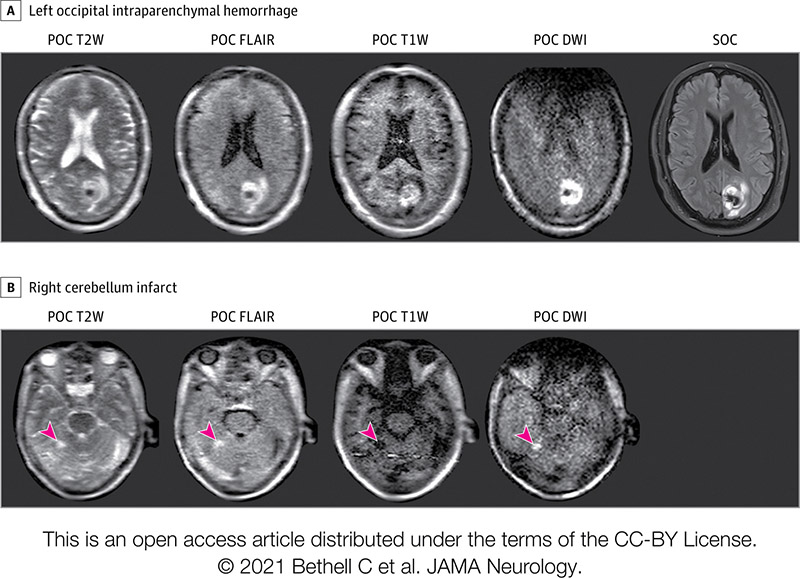

Practical challenges followed: Teaching people how to use the machine. Figuring out who to use it on. Ensuring there was no interference from or with other machines. Convincing everyone that repeated exposure to the magnet was safe. And, most of all, producing an image sharp enough to yield an accurate diagnosis.

Over two years, everything improved. That includes advances in the science of image reconstruction, the specialty that allows every generation of cellphone to take crisper pictures.

Two major milestones happened days apart: The FDA certified the device as safe and effective, and Kevin presented his findings at the AHA's International Stroke Conference.

Weeks later, the pandemic hit.

***

Many COVID-19 patients brought into Yale underwent portable MRI scans.

One such patient was non-responsive and connected to a ventilator. The next day, this patient was to have a breathing tube placed in their neck and a feeding tube in their belly. Then the portable MRI showed a massive stroke.

"We knew a stroke that size was not compatible with a meaningful outcome even if they survived," Kevin said.

The patient's family decided to skip the planned procedures. The patient died. A postmortem CT scan verified the massive stroke.

"The family was sad their loved one died," he said, "but grateful that we were able to get them that very important piece of information."

***

Imagine all the places the portable MRI machine can be used.

ICUs. ERs. Ambulances. Hospitals that can't afford a conventional MRI, especially those in rural areas or third-world countries. They could be brought to the homes of bedridden patients.

Kevin is especially intrigued by the ways it can be used, such as for immediate concussion evaluations at sporting events or the process of "serial imaging." Like time-lapse photography, a new picture could be taken at regular intervals – weekly, daily, even hourly – to monitor changes, such as whether a brain is starting to swell or if swelling is going down.

"Some people will go too far and say we can use it for everything," he said. "I would be the first to say, 'Don't overinterpret our results.' But I do believe this is more than an incremental change. It has the potential to be a game-changer."

***

Kevin obviously takes great pride in helping make possible something that NIH grant reviewers, and other skeptics, thought wasn't feasible.

He's also proud of his ongoing work with CHARM and ASPIRE, and the growth of his Yale division. A sign of how that's going: He recently received the Stroke Research Mentoring Award from the American Stroke Association, a division of the AHA.

His quest to answer bigger, better questions continues.

One of his next projects will study wearable stroke monitors. It's being launched through a Yale startup called Alva Health founded by Kevin and university colleagues Sandra Saldana and Hitten Zaveri, and it's funded by a major grant from the National Science Foundation.

Plus, he's again playing a key role in an AHA-backed project. Researchers from Yale, Mass General and University of California, San Francisco, are taking part in a hemorrhagic stroke study behind $11.12 million in funding from the Henrietta B. and Frederick H. Bugher Foundation. Yale's focus will involve treating high blood pressure, and looking at how genetics can help match the best medicine for each patient.

Saving and improving lives remains his focus. Yet he's also driven by the thrill of the hunt.

"Pursuing high-risk projects that match high-need opportunities is the attraction."

A version of this story appeared on Thrive Global.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].