Lower income linked to higher odds of clogged neck arteries

By Kat Long, American Heart Association News

People making less than $35,000 a year may be more likely to have carotid artery stenosis, a leading cause of stroke, a new study found.

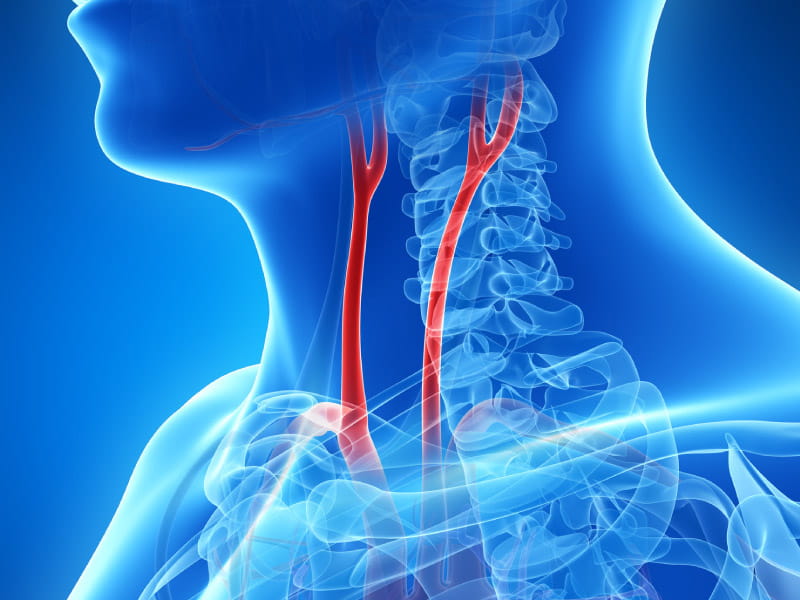

Carotid artery stenosis is a narrowing of the large arteries on either side of the neck that carry blood to the brain. The narrowing is often a buildup of sticky plaques. Known risk factors include high levels of "bad" LDL cholesterol, high blood pressure, smoking and diabetes.

Previous research shows Black and Hispanic people have a lower risk of carotid artery stenosis compared to whites, and Native Americans have a higher risk. But prevalence according to factors other than race and ethnicity is less clear.

To identify possible patterns, researchers evaluated electronic health records of a diverse pool of 203,813 participants in the National Institutes of Health's All of Us Research Program. Half of participants were white, 20% were Black, 20% were Hispanic, 3% were Asian and the rest identified as other races or ethnicities. One in 10 had less than a high school degree and 36% had a household income of less than $35,000 per year.

Overall, 2.7% of participants had been diagnosed with carotid artery stenosis. Among them, 7.3% had undergone revascularization, a surgical procedure to restore normal blood flow to the brain.

Those making less than $35,000 a year had 15% greater odds of carotid artery stenosis than those with a higher income. Lower income also was associated with 38% higher odds for carotid revascularization.

The findings, published in the journal Stroke, will be presented Thursday at the American Stroke Association's International Stroke Conference.

"Having a lower income may affect people's food choices," said Dr. Helmi Lutsep, professor and interim chair of the department of neurology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. She was not involved in the study. "They may not be able to buy healthy fruits and vegetables. And the more we learn about this, the more we can intervene and potentially change the pattern."

Lutsep said the study offers further evidence that doctors should be considering health disparities and using what they learn about their patients to guide preventive care.

When race and ethnicity were considered, Black and Hispanic participants had lower odds of carotid artery stenosis, echoing previous research. Black participants with the condition also were less likely to receive revascularization therapy.

"That could be due to less severe presentations," said lead author Dr. Daniela Renedo, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

So-called volunteer bias, which leads to more healthy people enrolled, might explain the lower rates of carotid artery stenosis in certain groups, the researchers said.

Even so, Lutsep commended the diversity of the study population, especially that 61% were women, because men are overrepresented in many stroke-related trials. But she also noted the potential for bias toward participants with access to computers in the All of Us Research Program, since enrollment appeared to be done mainly through its website.

Plenty of questions remain, Renedo said. But researchers will soon have access to the All of Us participants' genetic information, and "we will use these data to better understand the interaction between social determinants of health and biological factors that ultimately lead to carotid stenosis and its consequences."

The takeaway message for now, she said, "is that more attention should be given to the present health care disparities in this condition."

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].