Some questions answered, others raised in heart testing for mild chest pain

By Melissa Weber, American Heart Association News

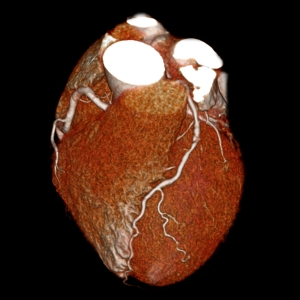

Millions of Americans visit their doctors complaining of mild chest pain. Most are given one of two types of heart exams: a traditional stress test to see how the heart reacts to physical activity, or a state-of-the-art CT scan that provides 3-D images of the heart’s arteries.

Which is best at predicting future heart problems stemming from the mild pain? It’s essentially a tie, according to the first clinical trial to comparing the two tests.

Patients who had a CT angiogram — a test that uses X-rays and a special dye to find coronary artery blockages — were no less likely to have a heart attack, be hospitalized or die from any cause within two years than those who had a stress test, according to findings presented in March at the American College of Cardiology’s annual meeting and published in the New England Journal of Medicine(link opens in new window).

The results came from about 10,000 patients observed through a federally funded clinical trial called PROMISE, short for Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain. The study did not include patients who went to the emergency room for chest pain.

Some doctors have used the high-tech CT scans for a decade without knowing whether they were any better than the older stress tests(link opens in new window) that evaluate the heart’s response to exertion. Experts now say the new study signals to doctors that they can keep doing whatever they’ve been doing.

“Either test is acceptable based on PROMISE,” said Eric Peterson, M.D., director of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, North Carolina, who was not involved in the research.

Before CT scans came along, the only way doctors could get a peek inside the heart’s arteries was through procedures that involved threading catheters directly into the vessels. Being able to inspect the heart’s arteries in a noninvasive way “was like the holy grail of cardiology,” said study investigator Daniel Mark, M.D., of the Duke Clinical Research Institute.

It is that level of precision that provided the CT test with its one advantage in the trial: more accurately identifying who needed follow-up tests and procedures.

Another study presented at the ACC conference and published in The Lancet(link opens in new window) echoed those findings. Researchers in Scotland found that among patients whose chest pain was thought to be caused by coronary heart disease, having a CT test changed the diagnosis for a quarter of them. (Chest pain can have other causes besides heart disease, such as indigestion or muscle injury.)

That meant doctors were able to stop giving unnecessary treatments to patients, said the study’s lead investigator David Newby, M.D., Ph.D., a professor at the University of Edinburgh.

“It really did mean you could stop a lot of treatment in people and say, ‘Your heart arteries are normal,’” said Newby. “What patients hate is when you say, ‘I think your heart arteries are normal.’”

Another surprise out of the PROMISE trial was its very low rate of bad outcomes, regardless of which test patients received. Only 3 percent had heart attacks or other problems during the two years of follow-up, researchers found.

That prompted some experts at the meeting to question whether far too many people with mild chest pain are undergoing heart testing. Rather, all that may be needed are medicines and lifestyle changes to treat risk factors such as high blood pressure, smoking or elevated cholesterol.

“The incidence of events was so incredibly low, why do any of these tests?” said Anthony DeMaria, M.D., a cardiologist at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the research. “If the goal is the reduction of events, why not just put the patients on medical therapy and have at it. It’s hard to do better than that.” Pamela Douglas, M.D., director of imaging at the Duke Clinical Research Institute, led the PROMISE study and said overtesting is a valid concern. The investigators plan to identify the subgroup of very low-risk patients who may not have needed testing, said Douglas.

Cardiologist Elliott Antman, M.D., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said he already gives certain patients the option to skip extensive testing and go straight to medications.

“But if you’re someone who wants to know more, or if you’re in a profession where your health impacts the health of others, like if you’re an airplane pilot or a bus driver, then maybe we should do more imaging to get an exact diagnosis,” said Antman, president of the American Heart Association and a professor at Harvard Medical School.

The AHA guidelines currently recommend stress tests over heart CT scans for diagnosing heart disease. However, a CT scan may be the better upfront option if it is extremely likely that a person has severe heart disease that will require an artery-opening procedure, according to the 2014 guidelines. A CT scan may also be used if results from a stress test are unclear, the guidelines said.

And most cardiologists are choosing a type of stress test that involves more radiation than a CT scan, the PROMISE trial found. Only a third of doctors chose an exercise ECG or stress echocardiogram, neither of which involve radiation. The remaining two-thirds of patients got a nuclear stress test, in which a radioactive dye is injected into a vein and a gamma camera produces images of the heart.

Nuclear stress tests are also the most expensive to perform, costing providers $946 to $1,132, according to an economic analysis of the PROMISE trial, also presented at last month’s ACC meeting. CT scans cost about $400, compared with roughly $500 for a stress echo and about $175 for a stress ECG.

“Exercise ECG in the United States is, for cardiologists, not really considered a viable test unless you really don’t have a suspicion of coronary disease at all,” said Mark, who led the financial analysis. “Cardiologists like the higher-tech, more precise imaging, and that’s why the study reflects what it does.”

Although the economic study did not look at patient’s out-of-pocket costs or reimbursements to providers, experts said many insurers are more likely to pay for stress tests than heart CT scans.

Vietnam War.

Duke’s Peterson said that although he expects a slight increase in the use of heart CT tests nationwide, “physicians and patients should decide together which test is best, while also considering which test your center does best,” said Peterson, also an AHA volunteer.

Larry Greenwold, a 73-year-old former Marine bombardier, participated in the PROMISE trial and underwent an exercise stress test in 2011 after experiencing recurring chest pain. Doctors found that one of the arteries supplying blood to Greenwold’s heart was blocked. Two stents were needed to reopen it.

“With what they saw on the exercise stress test, they were able to be pretty confident that I had a blockage,” said Greenwold. “That was good enough for me.”

Image courtesy of Toshiba America Medical Systems. Photo courtesy of Larry Greenwold.