Why a sportswriter's sudden death should lead you to ask about your own family history

By Michael Merschel, American Heart Association News

The sudden death of celebrated sportswriter Grant Wahl at a World Cup match in Qatar last week shocked those who knew him – and of him. He had just turned 49 and seemed healthy, aside from recent complaints about chest pressure, which he attributed to exhaustion and bronchitis.

On Wednesday, Wahl's family said he'd died from the rupture of an undetected ascending aortic aneurysm. "No amount of CPR or shocks would have saved him," his wife, Dr. Céline Gounder, said in an online post.

The condition is rare but not unheard of, said Dr. Eric Isselbacher, director of the Healthcare Transformation Lab and co-director of the Thoracic Aortic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. An aortic tear killed actors John Ritter at age 54 in 2003 and Alan Thicke at age 69 in 2016. JPMorgan Chase bank CEO Jamie Dimon, then 63, survived an aortic tear in 2020.

"One of the challenges is that it's not well known about in the public, and even some physicians aren't very familiar with it," said Isselbacher, who is also an associate professor at Harvard Medical School. He led the writing committee that crafted new guidelines for aortic disease treatment, which were issued in November by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology.

Wider understanding – particularly about the importance of family history – could save lives, Isselbacher said. So here are things to understand about aortic aneurysms.

What is an aortic aneurysm?

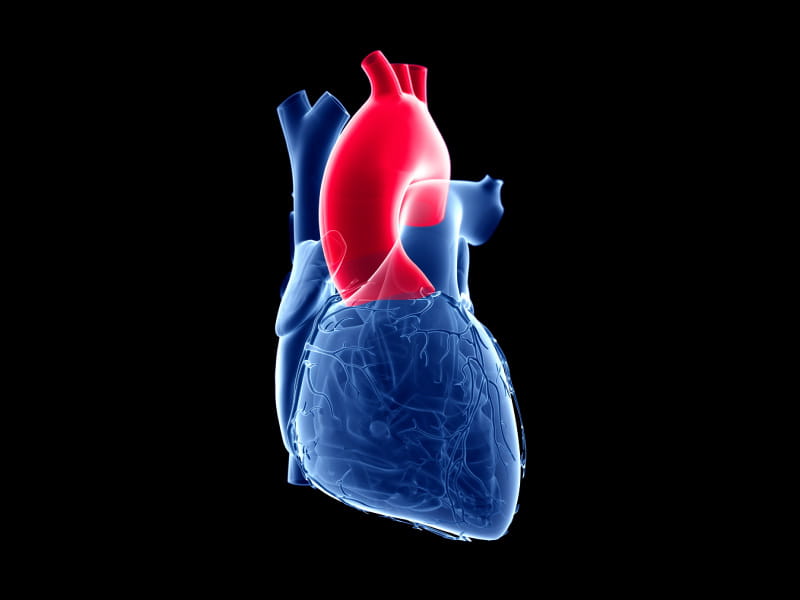

The aorta is the largest artery in the body, carrying oxygen-rich blood from the heart, which the aorta arcs over like a candy cane. The ascending aorta goes up the left side of the heart; the descending aorta stretches down into the abdomen. The aortic arch connects them.

An aneurysm is a ballooning or weak area in an artery, said Dr. Ourania Preventza, a cardiac surgeon at the Texas Heart Institute in Houston. She's also a professor of surgery at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and was vice chair of the committee that wrote the new aortic disease treatment guidelines.

Does an aortic aneurysm have symptoms?

"Not necessarily," Preventza said. If the aorta ruptures, or dissects, "people can die on the spot."

But that's not the usual course of events, Isselbacher said. "The typical story is, 'I was at the kitchen sink, washing the dishes, and it felt like someone stabbed me in the back."

Other symptoms may include chest pain or pressure, and neck or jaw pain. It's similar to what's reported with heart attacks, Isselbacher said, although heart attack pain tends to start off moderately and get progressively worse over time. Aortic dissection pain can be sudden and severe.

"Heart attack pain tends to be a tightness, pressure, burning – one of those words," he said. "Dissection tends to be sharp, stabbing, ripping."

If you have such symptoms, don't waste time pondering, Preventza said. Get to an emergency room.

Who is at risk?

The rate for aortic aneurysms is five to 10 per 100,000 person-years, according to the treatment guidelines. For the part of the aorta that descends into the abdomen, risk factors include being male, smoking, high blood pressure and high cholesterol – "the same risk factors that are actually associated with a heart attack," Preventza said.

But an aneurysm connected to the ascending aorta is different, Isselbacher said. It is related to abnormalities that a person had at birth and grows slowly over a lifetime. "The problem then is that a perfectly healthy person who might run every day and eat a good diet can have one," he said.

People born with bicuspid heart valves – that is, valves with two leaflets instead of three – are particularly at risk. Bicuspid heart valves happen in about 1% of people, Isselbacher said, and about half of them will have an aortic aneurysm.

Family history is extremely important, Isselbacher said. "If you have one of these aneurysms, there's a 20% chance that other family members will have it as well."

How is an aneurysm discovered?

It's often by chance that an aneurysm is found when a doctor does a scan for something else, which is part of why knowing your family history is so important.

For the immediate family members of anyone who had an ascending aortic aneurysm or an aortic tear, an imaging test is "essential," the treatment guidelines say.

If imaging scans turn up an aneurysm in a young person, Isselbacher said, genetic testing for the family is in order.

What type of family history matters?

Isselbacher said anyone with a close relative who died young of a sudden heart event should consider getting screened, because those deaths often are not reported correctly.

"When someone dies of sudden death at a relatively young age, sure, it could be a heart attack, but it could also have been an aortic rupture. So, it's extremely important not to make assumptions."

Wahl's family did not discuss details of his health history.

How are aortic aneurysms treated?

Aneurysms can be monitored until they grow large enough to be worrisome, Isselbacher said. Medication might be used to lower blood pressure. Eventually, surgery may be required.

Preventza said that while the descending aorta can be operated on with minimally invasive techniques, the ascending aorta requires open-heart surgery.

Awareness of an aneurysm makes a huge difference in getting fast treatment when one tears, Isselbacher said.

"If you know that you have an aortic aneurysm, hopefully you've been instructed that if you ever get the sudden onset of severe chest or back pain that you need to go right to the emergency room" for a CT scan. He tells his patients to announce as they enter the ER, "I have an aneurysm in my chest," to ensure they get moved to the front of the line.

"Basically, the clock is ticking with an aortic dissection. The death rate is somewhere on the order of 1% per hour. So, if you stay at home and sleep it off, then you might not be there the next day. But if you get to the emergency room promptly, get a CT scan that makes the diagnosis and fix it. The odds are very good you'll survive it."

What's on the horizon?

Preventza said devices that would enable non-invasive repair of the ascending aorta are being tested but have not been approved.

Isselbacher said researchers need to find ways to screen people without expensive imaging, perhaps with a blood test or a better genetic test, and to better identify which patients with aneurysms need surgery most urgently.

What should someone who's worried about an aneurysm do in the meantime?

Tending to basic heart health matters such as not smoking and monitoring blood pressure and cholesterol and maintaining a healthy weight are important, Preventza said. She again stressed the importance of knowing family history. "Did my dad, my mom, my grandpa, my uncle – anybody in my family – die from an aneurysm? I should know that."

That lesson applies to health care professionals as well, Isselbacher said.

Even among those who understand the urgency of family history, follow-up action "is not well executed. People might mention it to a patient in the hospital, but they'll forget it, and never pass it along to their family members. But if all the doctors out there who treated patients with aneurysms made sure that family members were screened, we can certainly reduce the risk."

If you have questions or comments about this American Heart Association News story, please email [email protected].