Heart disease and aspirin therapy

By Melissa Weber, American Heart Association News

Aspirin is one of the oldest, best-selling and most familiar drugs around.

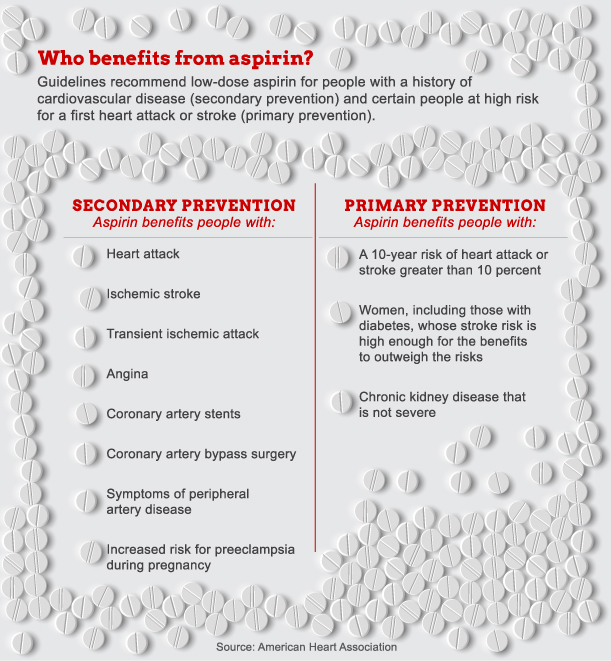

About one in five American adults regularly take aspirin, according to the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Many are heart attack and stroke survivors who take an aspirin a day to lower the chance of having a repeat heart attack or clot-related stroke — a strategy called secondary prevention. For this group, the evidence is clear that daily low-dose aspirin can be beneficial.

But for another group of aspirin-takers, the evidence is less compelling.

They are people hoping to prevent a first heart attack or a first stroke, and who use aspirin as a method of primary prevention. But recent studies suggest the benefits do not always outweigh the risks of daily aspirin use, which can include bleeding and other side effects.

“Aspirin is an effective and important treatment to prevent a heart attack or stroke in someone who has a history of heart disease or stroke,” said Mark Creager, M.D., president-elect of the American Heart Association and director of the Vascular Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “That’s not the case for the healthy person who’s at low risk for these events.”

Most heart attacks and strokes occur when blood flow to the heart or brain is blocked by a blood clot. Aspirin works by “thinning” the blood and preventing the formation of clots.

But aspirin can cause complications.

When blood cannot clot easily, excessive bleeding can occur. A burst blood vessel in the brain can cause a hemorrhagic stroke. Some people have bleeding in the stomach or elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract. Most side effects of aspirin include upset stomach and heartburn. More serious side effects are uncommon — but they can be life-threatening.

“Many people who take aspirin will notice it’s harder to stop the bleeding when they get a cut. But these people are also at risk for potentially catastrophic bleeding,” Creager said.

How aspirin should be used

Aspirin has long been a medicine cabinet staple. It is used to relieve pain, reduce fevers and calm inflammation. Then in the 1970s, aspirin’s reputation got a boost: Studies started finding that aspirin could also help prevent heart attacks and strokes in people who had already had one.

Research shows that among heart attack survivors, regular aspirin use can reduce the risk of a second heart attack, stroke or cardiovascular-related death by about 25 percent. For stroke survivors, it lowers the risk of a second event by about 22 percent.

For heart attack survivors, the risk of having another heart attack or a stroke is 4 percent to 5 percent a year, said Creager. “If you cut that risk with aspirin by 25 percent over five years, that’s pretty substantial,” he said.

(link opens in new window)

(link opens in new window)

View text version of infographic

Today, more than two-thirds of heart disease and stroke survivors age 40 and older take low-dose aspirin to prevent a recurrence, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Others also benefit from clot-preventing aspirin, including patients who get stents placed into heart arteries. Doctors often prescribe daily aspirin to prevent the stents from becoming blocked.

A new study, presented last November at the AHA’s Scientific Sessions 2014 and published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that long-term use of aspirin plus a second anti-clotting medication cut the risk of having a heart attack by more than half in people who had received a stent.

Daily aspirin not for everyone

Experts agree that aspirin can help thwart a second heart attack or stroke. Yet for those without such a history, research suggests the drug’s risks may offset the benefits.

That advisory came last May from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which warned that the over-the-counter drug should not be used for primary prevention of heart attacks and strokes.

The likelihood of having a heart attack or ischemic stroke is about half a percent a year among people without cardiovascular disease, noted Creager. “For them, aspirin has a very modest effect in reducing the risk of heart attack, and it may put them at increased risk for bleeding,” he said.

Indeed, a Japanese study recently found that among older people with high blood pressure, high cholesterol or diabetes — three major risk factors for heart attack and stroke — taking a low-dose aspirin every day did not reduce the overall risk of heart attack, stroke or death. Yet aspirin users had an 85 percent higher risk for bleeding inside the skull and were more likely to have gastrointestinal bleeding.

The findings were presented at the AHA’s Scientific Sessions 2014 and published in the Journal of the American Medical Association last November.

View text version of infographic

Because of the bleeding risk, AHA guidelines only recommend daily low-dose aspirin for primary prevention in people with a greater than 10 percent risk of having a heart attack or stroke within the next 10 years.

Creager helped write the AHA’s 2014 guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke and urges people to talk to their doctors about whether their individual risk is high enough to warrant aspirin therapy or a similar drug. “If you’re healthy and at low risk, you should not be prescribed aspirin,” said Creager. “But if your doctor does prescribe it, you need to understand why.”