Her father's death fuels a lifelong push to understand South Asian heart health

By Michael Merschel, American Heart Association News

Dr. Latha Palaniappan, an internal medicine doctor and professor of cardiovascular medicine at Stanford University in California, has won accolades for her work, much of which has involved using huge databases to uncover and explain differences in heart disease among underrepresented groups, particularly Asian Americans.

Those professional interests stem from a deeply personal loss.

"My dad died from a heart attack at 39, when I was 13," she said. "I am motivated every day by what happened to my father and my family, and I want to make sure that other families don't experience early heart disease. I find this is particularly devastating to immigrant and minority families."

Palaniappan, who is co-founder of the Stanford Center for Asian Health Research and Education, talked about her work as part of "The Experts Say," an American Heart Association News series where specialists explain how they apply what they've learned to their own lives. The following interview with her has been edited.

You've done groundbreaking work in understanding health differences among Asian Americans. Why is it important to understand the diversity encompassed by that label?

Asian Americans are the fastest-growing broad racial group in the nation, making up about 7% of the U.S. population and comprising more than 40 ethnicities who speak over 100 languages. Despite this large diversity, health research often lumps Asian American groups together, which masks important differences in health risks.

Asian health research also received less than 0.2% of total funding from the National Institutes of Health between 1992 and 2018. As a result, there isn't enough data to guide health professionals.

How does cardiovascular disease and its risk factors differ among Asian American subgroups?

Research in the U.S. shows South Asians in particular – including people from Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka – have a higher proportional death rate from ischemic heart disease (which blocks coronary arteries and can lead to heart attacks) than non-Hispanic white people. A global study found people in South Asian countries also tend to have heart attacks at younger ages compared to people in other countries.

Yet while Asian Indians, for example, have a 33% higher ischemic heart disease mortality, Vietnamese people have more than 70% higher mortality from stroke and other cerebrovascular diseases compared to non-Hispanic white people.

Asian Indians and Filipinos, meanwhile, have a higher prevalence of diabetes compared to other Asian groups and non-Hispanic white people. Filipinos have a higher prevalence of high cholesterol, high blood pressure and obesity. Among South Asians, there is lower muscle mass, and fat is often concentrated on the liver and around abdominal organs, which may explain the higher prevalence of diabetes.

You began looking into South Asian health issues early in medical school. Was much information available?

No. For much of my early medical education in the late 1990s, disaggregated data on Asian Americans, let alone South Asians, was minimal.

Asian Americans weren't consistently mentioned in the literature and were often grouped under the "other" race category. Before 2003, only seven states required the reporting of specific Asian ethnic groups, including California.

How has what you've studied in the years since then affected you personally?

It has been a long road and I have been working on this problem with cardiovascular disease in minorities and South Asians specifically for 20 years. To be honest, when I was a medical student, I thought I would've had it figured out by now. But I realize that there is still so much work to do, and it will take teamwork to solve these disparities.

I still find myself frustrated as a physician that when I have patients from historically underrepresented groups, all of the data that I use to inform my treatment decisions are on white populations. I don't think that I can offer personalized precision health to certain groups because there's not enough data. I have no guidance on what drugs might work for Hispanic, African American, Native American or specific Asian populations. There are known differences in drug metabolism, outcomes and side effects, and I often feel like I'm flying blind.

Given what happened to your father, do you talk with family members about their risks?

I talk to everyone I meet about their risk!

My husband is also South Asian and inherited high cholesterol disorder from his mother, who had early strokes and unfortunately recently passed away due to a stroke.

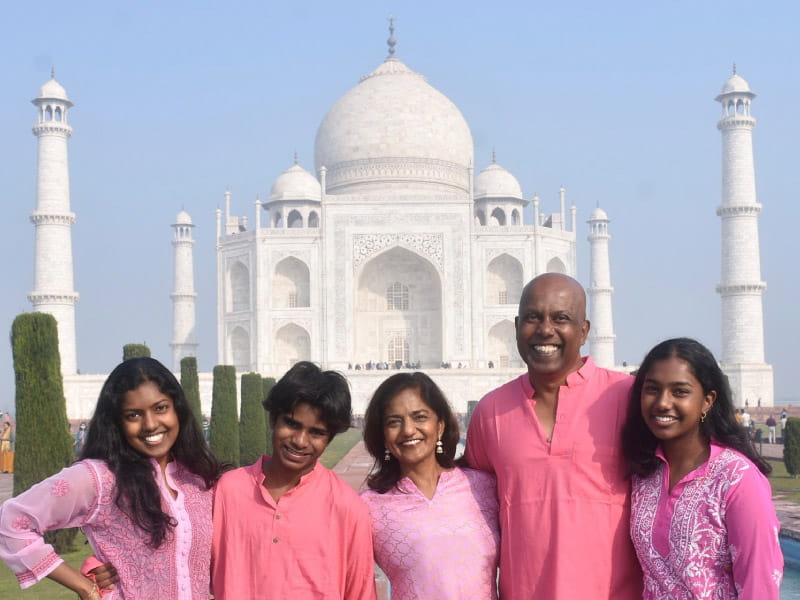

My kids are ages 15, 19 and 23. My 23-year-old daughter has inherited the high cholesterol disorder from her father. My 15-year-old son is adopted from India, and we have very little information on genetics within South Asian communities generally. About 80% of genetic studies are performed in white European populations, which represent roughly 16% of the global population. In contrast, 25% of the global population is South Asian, and genetic data is scarce.

This hopefully will be addressed by several new initiatives, including the OurHealth study, which is a national study of health and genetic information of South Asian adults to better prevent cardiovascular disease. There's also the MOSAAIC study, which is a cohort of 10,000 Asian, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander adults who will be followed over time to discover predictors of cardiovascular disease.

No one researcher or institution can solve this problem alone. It's so important that we collaborate to create precision health for the next generation.

You started your career doing extremely personal medicine, working in Southeast Asia in an East Timor refugee camp. Today, your work involves crunching massive amounts of data. What's the connection between those extremely different tasks?

My work in East Timor was extremely rewarding. Working with Doctors Without Borders in a humanitarian crisis was incredibly fulfilling every day in every way. We were helping people in immediate need with emergency aid and medical care.

In contrast, working with data is more abstract, but can affect many more lives. Most decisions around Asian health are made using mainly non-Asian data. By analyzing and learning from data from sources such as national datasets, electronic health records and genetic/pharmacogenetic testing, we can find patterns in disease risk and outcomes.

By integrating cutting-edge advancements in data science and computing, we can provide uniquely tailored care for each patient and expand the horizons of medical science for everyone.