Shorter chromosome caps may predict stroke, dementia

By American Heart Association News

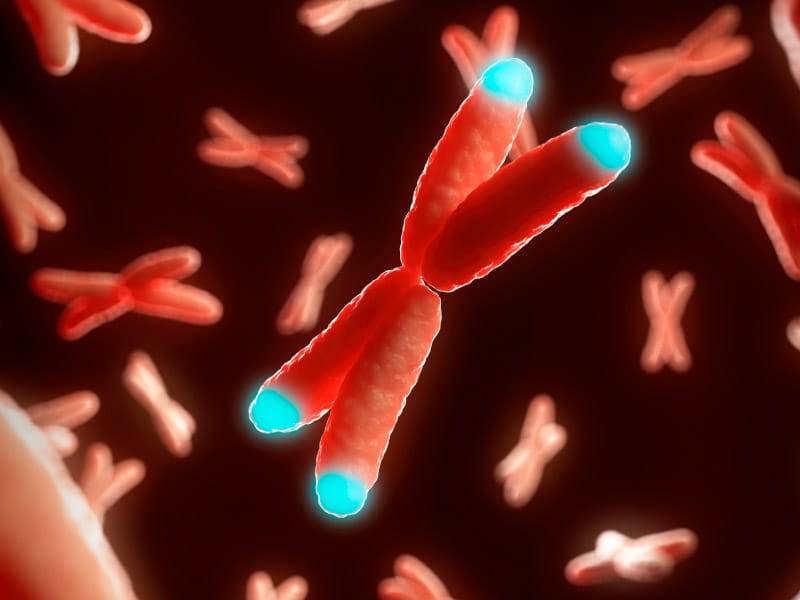

People with shorter telomeres, the protective caps at the end of chromosomes, inside their white blood cells may be more likely to have strokes or develop dementia and late-life depression, new research suggests.

But lifestyle behaviors – such as eating a healthy diet and staying physically active – may help reduce that risk, the study found. The findings were presented this week at the American Stroke Association's International Stroke Conference in Los Angeles. The findings are considered preliminary until full results are published in a peer-reviewed journal.

No studies have examined how telomere length in white blood cells, or leukocytes, affects age-related brain diseases that include stroke, dementia and late-life depression, Dr. Tamara N. Kimball, one of the study's co-investigators, said in a news release. Kimball is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Henry and Allison McCance Center for Brain Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

"All three conditions are linked to cerebral small vessel disease, a condition associated with aging and accumulation of vascular risk factors," she said.

Leukocyte telomeres gradually shorten with age, lowering their ability to protect genetic material inside the chromosome. This leads to greater cell aging and increased susceptibility to age-related diseases. Telomere length can be affected by genetics, ancestry and gender, which cannot be changed. Other factors that affect length – such as lifestyle choices and environmental stressors like pollution – can be modified.

"In a clinical setting, leukocyte telomere length could help identify people who may need more intensive monitoring or preventive measures," Kimball said. "It could also guide personalized interventions, including lifestyle adjustments and therapeutic approaches, to enhance overall health."

However, because the evidence linking leukocyte telomere length to stroke risk is still exploratory, Kimball said her team is not suggesting using that measurement as a standard practice.

In the study, researchers analyzed data from 356,173 participants in the UK Biobank, a large population-based study drawing people from 22 health centers in the United Kingdom. Participants were recruited from 2006 to 2010 and were an average 57 years old at the start of the study. Their blood samples were used to analyze leukocyte telomere length, and the measurements were divided into groups: shortest, intermediate and longest.

A Brain Care Score assessment quantified their modifiable risk factors such as blood pressure, diet, exercise, stress and the strength of social relationships. None of the participants had been diagnosed with stroke, dementia or depression at the time of enrollment.

Over a median 12 years of follow-up, people with shorter leukocyte telomeres on their chromosomes had an 11% higher overall risk of developing at least one of the three age-related conditions, compared to those with longer caps. They had an 8% higher stroke risk, 19% higher dementia risk and 14% higher risk for depression diagnosed at 60 or older.

The analysis, Kimball said, also suggested that healthy behaviors could lessen the risks associated with telomere length.

Shorter leukocyte telomeres were linked to an 11% increased risk for stroke, dementia and depression in people with low Brain Care scores, which suggests they engaged in fewer healthy behaviors and had more risks. Conversely, among people with high scores – which suggests healthier lifestyle choices and better risk profiles – shorter telomeres were not associated with an increased risk for any of the three brain diseases.

Kimball noted there was no evidence that the shorter telomere length caused the conditions, only that they were related. Instead, telomere length "may act more as a reflective marker of underlying biological processes and cellular stress that precede these age-related diseases," she said.

The findings, she said, also suggest that "adopting healthier lifestyles and improving modifiable risk factor profile may lower the negative effects of shorter leukocyte telomeres. In short, it is never too late to start taking better care of your brain."

The researchers noted the study had limitations. Telomere length and Brain Care scores were only measured at the beginning of the study, so any changes in length or lifestyle behaviors were not considered. The study also focused solely on people with European ancestry, so the results might not be applicable to other populations.

However, the findings do shed light on the mechanisms involved in the aging process, Dr. Costantino Iadecola said in the news release.

"While the link between aging and stroke, dementia and late-life depression is well established, the finding that telomere shortening in white blood cells can be a sign of aging holds significant clinical implications for assessing risks and predicting health outcomes," said Iadecola, director and chair of the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. He was not involved in the study.

"Recent research shows that different parts of the body age at different rates, each with its own 'aging clock,'" Iadecola said. "Evidence suggests that longer telomeres in white blood cells are connected to a lower risk of major brain diseases related to aging. This indicates a strong link between the aging clock of the immune system and the brain."