After 2 heart surgeries, jiu-jitsu gave him strength. Then his son was diagnosed.

By Deborah Lynn Blumberg, American Heart Association News

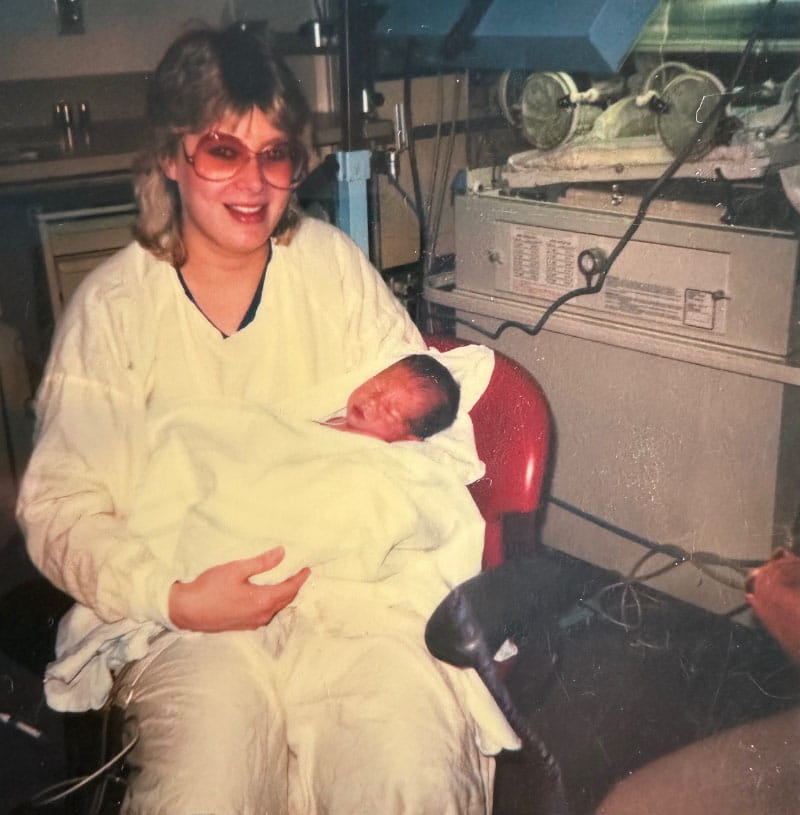

The morning after Dana Archer gave birth, her doctor rushed into her hospital room. "Your baby doesn't look right," he told the 20-year-old mom.

Overnight in the nursery, Chris Kidwell's skin had turned purplish-blue. It was a sign his heart wasn't pumping enough oxygenated blood to the rest of his body.

Testing showed Chris had a rare, life-threatening heart defect: His aorta and his pulmonary artery were switched. The aorta is the main artery carrying blood away from the heart, and the pulmonary artery carries blood from the heart to the lungs.

His oxygen saturation, or the percentage of oxygen in his blood, was 30% when it should have been in the 90s. Chris needed emergency surgery to fix the structural problem, allowing his blood to flow the right way.

At 6 days old in 1987, he had an arterial switch operation. As the name suggests, a surgeon switched the arteries to their correct locations.

Chris' surgery was a success. He recovered quickly, then settled into yearly checkups. One of his few limitations was avoiding contact sports because a direct hit to the chest could damage his heart.

Growing up in French Lick, Indiana, Chris lived vicariously through the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. He loved martial arts and frequently staged elaborate karate matches with his Ninja Turtles action figures. Michelangelo was his favorite character for his goofiness and love of pizza.

At age 3, Chris jumped off his bed pretending to be a wrestler, and broke his calf bone. He got a green cast, and Dana drew Ninja Turtles on it. When Chris turned 5, he was thrilled to have a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles cake at his birthday party.

Then, at 11, Chris got upsetting news from his doctor. Scar tissue from his first surgery had caused his pulmonary artery to narrow. He needed another operation.

The surgery went well, as did the recovery. While many patients take a few weeks to recover from open-heart surgery, Chris returned home on a Saturday evening, just a few days after his procedure.

His health was good through high school, into college and then in his 20s as he worked as a family case manager and then as an intelligence analyst at a state agency that analyzes and shares information about potential threats to public safety. Chris committed to eating healthy and exercising.

When he turned 30, the itch to do martial arts was still strong. He couldn't ignore it anymore. He learned that Brazilian jiu-jitsu is grappling-based and doesn't involve direct strikes to the chest. His continued research led him to become inspired by grapplers like Hélio Gracie, who went from a sickly child to a jiu-jitsu legend, and Jean Jacques Machado, who was born missing fingers on his left hand.

Chris began studying and practicing jiu-jitsu, first at a local academy and then at home on his own through instructional videos. He checked in with his doctor, who told him he only had to worry about the heart issues everyone needs to be aware of as they age: high cholesterol and high blood pressure. As he continued to spar, he often beat opponents who were twice his body weight and had more experience.

Along the way, he started teaching jiu-jitsu to local kids.

Seeing them develop in and out of the academy inspired Chris, now 37, to return to school; he earned his doctorate in education. His research looks at how jiu-jitsu contributes to people's holistic development.

One of his pupils is his son, 9-year-old Carter. The two often grapple together in 160 square feet of mat space at their home in Orleans, Indiana.

Two years ago, the two learned they have another unique connection: Carter has a congenital heart defect, too.

During a wellness checkup, Carter's doctor heard a swooshing sound in his heart. Further testing showed that Carter had a hole in his heart. It was an atrial septal defect, or a hole between the heart's upper chambers.

Leading up to the procedure to fix Carter's heart, Chris played a song he was fond of from the 1990s: "Lullaby" by Shawn Mullins. The line "Everything is gonna be all right" comforted both Chris and Carter as they prepared for surgery.

Last spring, Carter had a procedure to close the hole in his heart at the same hospital where Chris got his care. Now, Carter is doing well, and he doesn't have any physical restrictions. Unlike Chris, he can play contact sports if he wants to.

These days, Chris, Carter and Dana enjoy doing outdoor activities together, like kayaking long distances on the nearby Blue River in Milltown.

Chris is thankful every day for his health and for his ability to be active, especially since he knows that some people with his condition often end up needing a pacemaker by adulthood. "I'm so fortunate and grateful to be blessed with the life that I have," he said.

To other parents of children with a heart defect, Dana said: "Talk to the doctors, find out what they can and can't do, and then just have faith that things will be all right."

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.