Sepsis is a lesser-known threat to heart health

Sepsis, the body’s extreme reaction to infection, is a common illness that’s often misunderstood but can have a big impact on your heart.

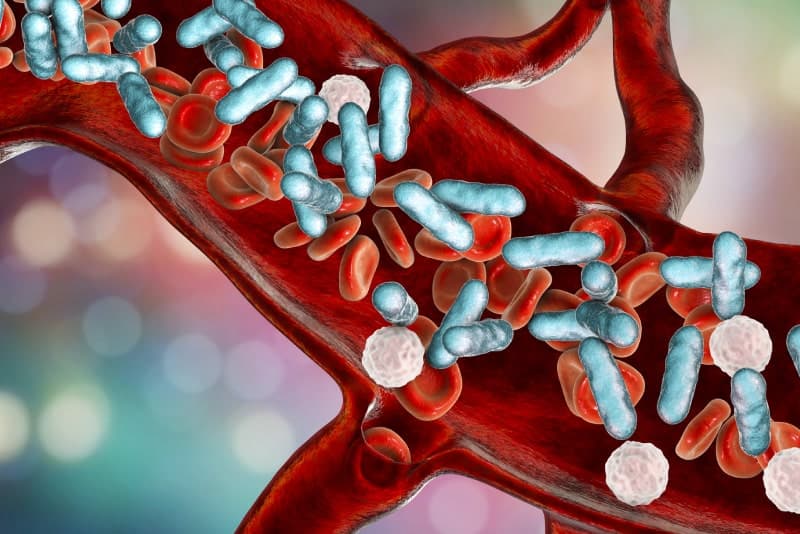

Most cases can be blamed on bacteria. But viruses, including the flu and the virus that causes COVID-19, also can spark it, as can fungal infections.

According to Dr. Henry Wang, professor and vice chair for research in the department of emergency medicine at the Ohio State University in Columbus, all infections "can make the body overreact and can make the body very irritable and inflamed. And those toxins end up in your bloodstream and start to poison all the organs of the body."

That means sepsis is entwined with the cardiovascular system and can endanger the heart, sometimes years after a person has been ill.

"For example, a common thing that happens when you get an infection is that the blood vessels dilate," Wang said. "That's an overreaction to the invasion of the infection in the bloodstream. And because of that, your blood pressure drops." The body then struggles to deliver adequate blood and oxygen to vital organs.

Sepsis also damages the lining of the blood vessels, Wang said, making the person susceptible to blood clots and causing other problems that are "big players in heart disease," such as inflammation.

Wang's research published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases suggests people hospitalized for sepsis were twice as likely to have or die from a future coronary heart disease event, such as a heart attack, as people without a history of sepsis. That risk remained elevated for at least four years.

Other research in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine shows 10% to 40% of people with sepsis end up developing a type of irregular heartbeat called atrial fibrillation.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, at least 1.7 million U.S. adults develop sepsis yearly, and nearly 270,000 die as a result.

Sepsis may be especially dangerous for people with heart failure, where the heart does not pump properly. A study in the Journal of the American Heart Association found sepsis may account for almost a quarter of deaths in people with heart failure who have reduced heart pumping function.

It carries long-term effects, Wang said. "We're realizing that there's a whole sepsis survivor syndrome that's been completely underrecognized in our field."

Impaired brain function can be one serious after-effect, said Wang. He led a study published in Critical Care Medicine that found the rate of cognitive decline accelerates about sevenfold after sepsis.

Doctors continue to struggle in spotting the signs of sepsis, which can include a high heart rate or low blood pressure; confusion or disorientation; extreme pain; fever; and shortness of breath. But experiments using artificial intelligence have helped to spot the problem earlier.

A better understanding of who's at risk also could help, Wang said.

People 65 and older, people with weakened immune systems, and people with chronic conditions, such as diabetes and cancer, are at higher risk for sepsis, the CDC says.

Wang said people with kidney problems and vascular disease also have a higher risk, as do people with conditions that make them prone to blood clots. His work has linked obesity to sepsis risk too.

For something so common, it doesn't get a lot of attention, Wang said. "We could probably save thousands of lives a year and really improve the lives and quality of life for all the survivors if we dedicate a lot more attention to this condition."